Report Overview and Key Findings

By Luc Schuster

October 2024

Click Download button above to read the full report by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard and the design firm Utile.

Boston Indicators has long explored how zoning restrictions contribute to our region’s housing market challenges. Recent actions, like the 2021 MBTA Communities law and the Affordable Homes Act’s legalization of Accessory Dwelling Units, show some progress. But there’s a growing recognition that zoning reform alone won’t solve the housing crisis. That’s why Boston Indicators commissioned the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard and the design firm Utile to produce this report: Legalizing Mid-Rise Single Stair Housing in Massachusetts.

Among the non-zoning regulations that sometimes hamper new housing construction is the building code, an amalgam of regulations that should evolve with time and technology. But old concerns and considerations live on in the building code long after technological or architectural advances have overridden their safety value. For instance, engineered wood is restricted in taller buildings despite its proven safety, and overly large elevator requirements drive up costs.

This report focuses on staircases and the code requiring two separate stairways in mid-rise buildings. Advances in materials, smoke detection, and sprinklers have sparked a reconsideration of this rule across North America, and we examine the potential for change in Massachusetts.

Below is a synthesis of key findings from the report, roughly mirroring the report structure:

Shifting Housing Typologies Over Time in Greater Boston

In addition to triple-deckers, single-stair buildings were a common multifamily housing typology in Greater Boston up until the mid-20th century. Many are still in use today, especially in the Back Bay and Fenway. These buildings were well-integrated into the urban fabric and offered more compact, efficient housing solutions than modern double-loaded designs.

Over time, as building codes began requiring two modes of egress, the podium building became the more dominant multifamily housing typology in Greater Boston. This “five-over-one” design, which consists of five wood-framed stories atop a podium of steel or concrete, emerged to meet code requirements and maximize profit, sometimes sacrificing the goal of creating livable, diverse housing.

Downsides to the Current Dual Egress Requirement

- Inefficient Use of Space and Land: The dual egress requirement (i.e. two staircases) forces developers to design buildings with two staircases, typically connected by a double-loaded corridor. This limits flexibility in floor plans and results in inefficient use of space, especially on smaller parcels. Developers are incentivized to stretch buildings to maximize units around long hallways, leading to larger footprints and underutilized land in dense urban areas.

-

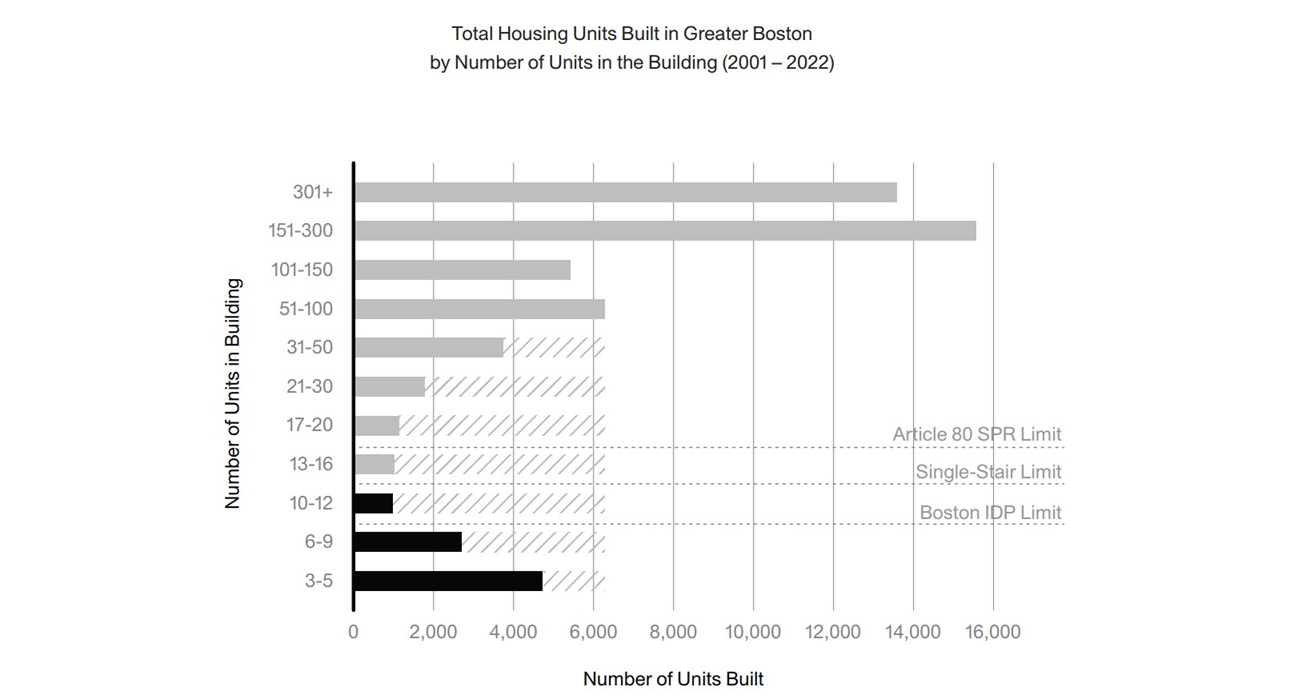

Reduced Housing Production, Especially on Small to Mid-Sized parcels: While double-loaded buildings provide high efficiency at larger footprints, they suffer greatly on small to medium sized parcels. Smaller parcels are abundant in Greater Boston—especially in the region’s most valuable, transit-rich neighborhoods—and these are often underdeveloped due to the inefficiencies associated with the dual egress requirement. Today, very few units in Greater Boston are created in buildings with more than nine but fewer than 30 units. Allowing for single-stair construction unlocks these parcels for developments that fit their scale, and pencil out.

The report estimates that we could net upwards of 130,000 new homes in Greater Boston using the recommended single-stair typology on undeveloped small-to mid-sized parcels within 0.75 miles of transit.

- Increased Construction Costs: The need for additional infrastructure driven by the dual egress requirements (e.g. steel framing and the second staircase) can add between 15 and 25 percent to the overall cost of a project, making smaller or more diverse developments financially unfeasible.

- Lack of Housing Diversity: The rigidity of the dual egress design makes it difficult to incorporate varied housing typologies, such as family-sized units or units with more natural light and ventilation. Most new housing becomes designed for efficiency rather than livability, leading to a focus on smaller units that are rented or sold at higher costs per square foot.

Point Loaded Potentials

- Enhanced Livability and Flexibility: Point Access Blocks (PABs), which use a single central staircase instead of long corridors with staircases at each end, offer more efficient and flexible layouts. They allow for better use of natural light, improved ventilation, and the opportunity for larger, family-sized units. Without long hallways, every unit in a PAB can have access to sunlight and fresh air, with windows on multiple sides.

- Unlocking Development on Smaller Parcels: Single-stair buildings are particularly well-suited to smaller and medium-sized parcels that are underutilized under the current dual egress model. These parcels, which are abundant in transit-friendly and walkable areas, could see increased housing production with single-stair designs that maximize density without sacrificing design quality.

- Increased Housing Diversity: Single-stair buildings allow for a greater variety of unit sizes and configurations, including family-sized units that are currently scarce in Greater Boston’s housing market. By avoiding the rigid hallway layout, developers can create more varied and livable spaces that appeal to a broader range of residents.

- Potential for Social Cohesion: Smaller, more compact buildings with fewer units (typically 24 or fewer) foster a stronger sense of community and social interaction. Without long hallways architects can design layouts that include better shared exterior spaces and courtyards, facilitating more regular engagement among neighbors.

Egress Code Landscape Outside of Massachusetts

- More Flexibility in International Codes: Countries like Switzerland, Japan, and many across Europe allow single-stair buildings up to six or nine stories tall. These countries have demonstrated that single-stair buildings can provide equal or better fire safety outcomes than in the U.S., despite the persistence of dual egress requirements.

- Successful U.S. Examples: Cities like New York, Seattle, and Honolulu have already implemented single-stair provisions for buildings up to five or six stories. These reforms improved construction efficiency, housing affordability, design quality, and the number of family-friendly units.

- Fire Safety in Single-Stair Buildings: Despite the perception that two staircases are essential for safety, data shows that countries with more relaxed egress requirements have comparable or better fire safety records. In the U.S., 99% of fire deaths occur in buildings without sprinklers, underscoring that sprinkler systems and modern fire-rated materials are more critical to safety than multiple exits.

- Momentum for Code Reform: Across North America, there is growing momentum to reconsider egress codes. California, Oregon, and Washington have passed legislation to allow single-stair buildings by 2025, and other states and provinces, including Ontario and British Columbia, are in the process of enacting similar reforms.

Proposed Reforms

Based on this research, the report outlines the following building code reforms for Massachusetts. These changes could be made by the Board of Building Regulations and Standards or through state legislation. Alternatively, the Legislature could enable municipalities to adopt the reforms individually at the local level.

- Legalize single-stair buildings up to six stories tall in Massachusetts, with a maximum of four units per floor. We propose doing this while maintaining other fire mitigation requirements, such as those for sprinklers and fire-treated materials, already in the building code.

- Reduce travel distance for egress by capping at 75 feet the maximum travel distance from the furthest point in a unit to the exit. This provision would make single-stair buildings as safe, if not safer, than larger podium buildings with longer travel distances to exits.

- Limiting floor plate size to 4,000 square feet per floor. This restriction ensures that buildings remain compact and efficient, further supporting the viability of single-stair designs on small and medium-sized parcels throughout Greater Boston.