Intensifying factors

During the moratorium, researchers & advocates warned about an eviction surge when protections expired. We have already returned to pre-pandemic eviction rates, and this upward trajectory could accelerate in the coming weeks due to a number of factors:

Rent debts continue to accrue. The Census’ Household Pulse Survey has been conducted for 17 weeks throughout the pandemic, asking respondents about rent payment status and likelihood of being evicted, among other housing and non-housing related questions. Based on the most recent survey data available (collected 10/14 - 10/26), roughly 14 percent of Massachusetts renter respondents were behind on housing payments, translating to an estimated total 161,000 households with rent debt. We know that these trends are not consistent across race and ethnicity, as both the health and financial impacts of the pandemic have deepened existing housing stability disparities by race. Based on the most recent Household Pulse Survey data, between 23 and 48 percent of Black renters and between 12 and 27 percent of Latinx households were behind on rent, compared with lower estimates for White (between 7 and 14 percent) and Asian renters (less than 12 percent).

Fear of eviction is high. Not all instances of rent debt result in an eviction. Some renters have worked out a payment agreement with their landlords. Others will apply for and receive rental assistance. Many may voluntarily leave if the likelihood of repayment seems grim, choosing to double up or move to a lower cost market where rent is more sustainable. For these and other reasons, not every household behind on rent will ultimately be subjected to a formal eviction process.

The Household Pulse Survey also asks respondents how likely it is that they will need to leave their home in the next two months due to eviction. Responses have varied over the past few deployments of the survey, but estimates have consistently shown tens of thousands of Massachusetts renters that are somewhat or highly likely to face eviction in the next two months and need to leave their homes. Using the 41,000 estimate from the most recent survey period, this number of evictions over a two month period would roughly translate to 4,700 eviction filings a week (using an approximate 4.3 weeks per month). This would far exceed any prior period of eviction filings. Of course, survey data should be taken with a grain of salt and it is highly unlikely that the pace of evictions will get even remotely close to this level. However, these data do indicate an extremely pervasive sense of anxiety and uncertainty among vulnerable renter households and a lack of confidence in the stability of their current housing arrangement.

Requests for assistance are on the rise. A recent spike in call volume to the state’s social service information hotline indicates that people have increasingly reached out with housing-related inquiries. This rapid increase coincides with the end of the state moratorium and the announcement of new emergency rental assistance money from the Baker-Polito administration (to be discussed later in this brief). The state’s marketing campaign, aimed at getting the word out about the availability of rental assistance, is a direct contributor to this increased call volume. Compared to pre-pandemic levels, the week of November 1 saw roughly five times as many housing and shelter related calls coming into the call center.

Some housing stability impacts can’t be tracked via formal eviction filings. Formal evictions that go through the court system are a small subset of the various ways tenants are coerced or forced out of their homes. Tenants will often leave on their own in order to avoid the trauma of defending their tenancy and avoid the potential adverse credit impacts of an unfavorable judgment. Outcomes for undocumented residents are particularly difficult to quantify, as immigration status adds an additional layer of anxiety and vulnerability when considering how to respond to a Notice to Quit. While we may not be able to quantify these outcomes, we know that informal evictions have occurred throughout the pandemic, even when the state’s eviction moratorium was in place.

Other potential factors not captured in eviction data include lease terms that ended without being renewed, small landlords that have sold their buildings when tenants moved out, and tenants that have been threatened with eviction or a small claims suit in a coercive effort to get them to move out. Tracking formal eviction filings will never address these known factors, and therefore we will only be able to quantify a portion of the housing stability crisis through conventional data sources.

Mitigating factors

While trends are worrisome, there are a number of protections, assistance programs and procedural delays that could buy time and preserve tenancy:

The CDC moratorium is still in place through the end of the calendar year. On Sept.1, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) announced a federal eviction moratorium would go into effect on Sept. 4. The eligibility criteria for tenants laid out by the federal moratorium is well summarized in this overview by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) and the National Housing Law Project (NHLP). The national moratorium will stay in place until Dec. 31, 2020. There can be no execution of judgments for protected households until after the start of the 2021. Landlords may be waiting until Jan. 1 to file for eviction, when the CDC moratorium ends and the rules surrounding the eviction process are clearer.

Emergency rental assistance is an incredible benefit for those who receive it. Rental Assistance for Families in Transition (RAFT) and other state and local emergency rental assistance programs are helping some residents repay rent debt and come to an agreement with their landlords that allows them to stay housed for the time being. New funding has been allocated to RAFT, the per-household limit has been increased from $4,000 to $10,000, and program enhancements have streamlined application processing. In recent months, the regional Housing Consumer Education Centers that administer the program have increased staff and have built capacity in response to increased need.

While not every household who needs rental assistance will receive it, these programs have a deep impact. For example, the expansion of up to $10,000 in assistance under RAFT also preserves tenancy for at least six months, or through June 30, 2021 for households with school-aged children. The security and predictability this provides, especially during a global pandemic, is enormous. More information on these changes and other components of the Baker administration’s response can be found on the state’s Eviction Diversion Initiative page.

Procedural delays could buy some time. The court process is slow, and new procedural changes aimed at mediation will add significant time to eviction proceedings. These modifications include an initial hearing that is focused on finding ways to keep the tenant housed, connect the parties to financial resources, and come to an agreement that satisfies both tenant and landlord. While a landlord has no legal obligation to approach mediation in good faith or accept a payment plan, this new process will likely keep some eviction filings from resulting in executed judgments against tenants.

Further upstream, prior to filing for eviction for non-payment of rent, landlords must deliver a Notice to Quit to tenants. For non-payment of rent, this is usually a 14-day notice, however, for certain properties that were protected under the CARES Act the Notice to Quit requirement is 30-days (the Act covers properties supported by HUD, USDA, and Treasury (Low Income Housing Tax Credit), and properties with federally-backed mortgages). This notice period allows time to for tenants to seek out rental assistance or come to a payment agreement, or at least preserve tenancy a little longer. Notices to Quit were prohibited by the state eviction moratorium, so the relatively low volume of new eviction filings in the first two weeks after the end of the moratorium could largely be attributed to this built-in waiting period. We do expect to see these numbers continue to rise in the coming weeks as more 14-day and 30-day notice periods end and turn into filings.

Patterns to watch

The housing stability crisis is unfolding and changing from day to day. As we track key indicators, here are some important questions and themes to keep in mind as we head into the unknown.

How quickly are existing rental assistance funds being disbursed? Who is receiving assistance? The largest rental assistance program in the state is the Rental Assistance for Families in Transition (RAFT), which has been the predominant vehicle for the state’s housing stability response. Even before the end of the moratorium, rental assistance funds were in heightened demand. Data collected by Metro Housing Boston, the RAFT administering agency for the Greater Boston region, showed that in the first six months of the pandemic (March to August) the number of RAFT recipients grew by 62 percent compared to the same period in 2019. Meanwhile, the median income of recipient households decreased dramatically (from $24,700 to just $3,084 for households without housing subsidies), average RAFT payments increased by 19 percent, and total payments under the program increased by 94 percent.

These changes occurred largely during a period of significant federal financial support, including the additional $600/week payments under the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program (FPUC), which ended in late July. While unemployment has come down somewhat from peak levels during the summer, employment has not returned evenly across industries, wage levels, or worker demographics. We know the need is still great, and federal financial support largely ceased at the end of July, putting immense pressure on the RAFT program.

In the coming weeks, demand for RAFT and other rental assistance programs is expected to increase even further. The courts have created a number of procedural mechanisms aimed at mediation during the formal eviction process. As more evictions are filed and enter the queue for mediation, we are likely to see an associated increase in demand for rental assistance.

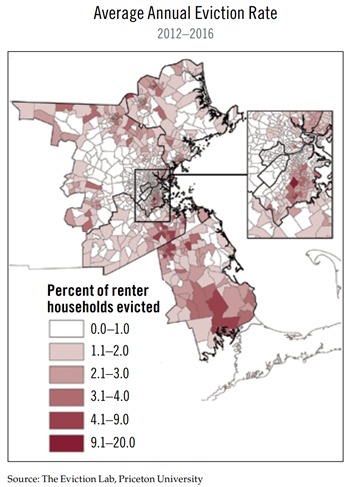

How closely will patterns of eviction follow existing patterns of inequity? Low-income households and communities of color are most at risk of eviction. This is true at all times, and this pattern is even more pronounced in times of crisis. Recent research by City Life/Vida Urbana and MIT in the City of Boston revealed that prior the pandemic, 70 percent of market-rate eviction filings are concentrated in census tracts where the majority of residents are people of color (despite the fact that only about half of the city’s rental stock is in these tracts). In the first few weeks of the pandemic prior to the state’s eviction moratorium, this figure increased to 78 percent. The report also highlights that eviction filings are even more likely to occur in census tracts where there is a larger share of Black renters.

We also know that these patterns extend beyond just the City of Boston. In our work on the 2019 Greater Boston Housing Report Card, we demonstrated that the census tracts with the highest eviction rates were more likely to be low-income with a majority of people of color. Neighborhoods in cities such as Lawrence, Lowell, Brockton and New Bedford have historically experienced high eviction rates.

We are likely to see similar patterns in the coming months, but potentially at a faster pace. Compounding these existing inequities are the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic, both in terms of health outcomes and job losses. As eviction filings rise, we will likely see them track with these other pandemic impacts. On our current course, we are heading toward deepening inequality and inequitable outcomes.

What role will the federal government play? Perhaps the most difficult trend to predict is the federal response to the pandemic, and when we might see a new federal stimulus package, if it all. It is hard to understate how critical a federal response is to stemming the rising tide of housing instability. The income supports provided by the CARES Act over the first four months of the pandemic were instrumental in replacing lost income. Key CARES Act provisions expired roughly four months ago, and the need has not diminished.

It is unclear how a new administration and a new congress will respond. What is clear is that a bold, comprehensive federal response to the pandemic and economic crisis would go a long way toward achieving better housing stability outcomes and changing the current trajectory of eviction filings.

One month after the moratorium, evictions on the rise.

By Callie Clark, Tom Hopper, and Lucas Munson MHP Center for Housing Data

November 23, 2020

Since April, our team has been reporting on housing stability, including ability to pay, rent collections, layoffs, eviction filings and the ever-changing patchwork of legal protections and supports for households facing the financial impacts of the pandemic. We’ve also tracked projections for the scale of the potential demand for rental assistance from research institutions, all of which built the expectation for a wave of potential eviction filings once the state’s moratorium ended on October 17.

Here we are, about one month since the protections provided by the state moratorium ended. What trends are we seeing emerge? What might happen next? What should we be tracking? This brief will provide an initial look at recent eviction filing trends, discuss potential intensifying and mitigating factors, and highlight trends we’re keeping tabs on as the crisis develops.

A good place to start is the absolute number of new eviction filings for non-payment of rent made since the moratorium ended. After months of just a handful of eviction filings during the moratorium (none of which were for non-payment of rent), new weekly filings have trended upward. An average of 608 filings per week were made in January and February, the two months just before the pandemic came into full swing. Last week (Nov 16 – Nov 20) 689 new eviction cases were filed for non-payment of rent, surpassing that average.