The Growing Wave of Federal Immigration Restrictions: What's at Stake for Massachusetts?

June 2019

Preface

The Boston Foundation opened its doors in 1915, at a time when immigrants were pouring into the city—more than 11,000 arrived in that year alone. The majority came fleeing poverty and unrest in Italy, Poland, Greece and Eastern Europe. They joined many others from Ireland, China and other countries, all seeking the promise of America. Most brought their belongings in just one trunk, lacked English language skills and desperately needed jobs. The Boston Foundation was founded in part to assist these newcomers by funding the settlement houses and other agencies that were responding to their needs and helping our entire city cope with the intensifying problems of urban modernity.

Today, immigration is again one of the Foundation’s primary concerns. Prior research has shown that essentially all of Greater Boston’s population growth since 1990 can be attributed to the arrival of immigrants. Most of today’s newcomers are from Asia, Central and South America, Africa, Haiti and other Caribbean countries. And, as in the past, our region’s economic success owes a tremendous debt to the innovation and energy they bring. At the same time, there has rarely been a time in our country’s history when immigration has been the target of such heated rhetoric and harsh restrictions

It is precisely for this reason that the Boston Foundation joined the Greater Boston Immigrant Defense Fund in 2017. Two years later, in collaboration with the Fund and Boston Indicators, we came together to produce this timely research.

It is worth noting that no immigration law has changed recently. But, due to the high degree of executive discretion that is enshrined in federal immigration policy, the president of the United States can make rapid and unilateral adjustments to the ways that immigration is regulated. What this report shows is that the current administration has taken that discretion and, in the guise of cracking down on unlawful immigration, exploited it through sweeping executive actions.

These executive actions have in practice targeted legal immigration—often in complex, nuanced ways. The administration’s actions, under the leadership of President Trump, have stretched the interpretation of immigration law so far as to cause courts to question their legality and issue numerous injunctions, stays and restraints.

Understanding how these changes have an impact on our local community is critical to developing and supporting advocacy and local policy interventions that can protect our neighbors and co-workers. The barrage of immigration restrictions and the intense pushback from the courts make it difficult for immigrants and their advocates to comprehend and respond to them—and to determine their impact on Massachusetts.

We hope that the cogent distillation of key areas of immigration policy presented in this report will help to clarify this complicated landscape and inspire new approaches to remedying the situation in ways that are imaginative and effective. We also hope that it will contribute to the national conversation about how to navigate these unsettling times.

Paul S. Grogan, President and CEO, The Boston Foundation

INTRODUCTION

The United States is a nation of immigrants, a place where people for centuries have come in search of opportunity, safety and liberty. Immigrants have made enormous contributions to American society, culture and economic vitality, and truly define what is great about our country. Despite that, well-established immigration practices have come under heavy attack by the Trump administration. This report describes the administration’s actions and details their impact on the lives of immigrants living in Massachusetts.

For years, international migration has stabilized populations in cities and towns across the country, counterbalancing domestic out-migration and industrial decline in several Northeast and Midwest cities, keeping those communities productive and vital.1 What’s more, despite paying taxes, immigrants utilize public benefits at significantly lower rates than the general population. They are also associated with lower crime rates and are more likely to start new businesses.2,3 Looking ahead, immigrants are poised to be the prime drivers of growth in the U.S. working age population as Baby Boomers retire.

Over many years, our government has built a set of immigration programs (flawed though they are) designed to enable immigrants to more fully participate in American life. For example, some of the supports provided by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) programs (both of which we describe later in this report) include:

- temporary legal status

- work authorization

- access to a Social Security number

- access to a driver’s license or state-issued ID

- ability to pay in-state tuition at state colleges and universities

Refugees and asylees who are fleeing violence in their home countries receive these aforementioned benefits. In addition, after one year in the United States, they may apply for permanent residence and can eventually become naturalized citizens. Most immigrants, including DACA and TPS holders, are ineligible for federal public benefits, with limited exceptions. However, refugees and asylees may access some federal benefit programs, and some states provide limited benefits to immigrants who may not qualify for federal programs.

Reversing generations of efforts to integrate new immigrants into our communities, the Trump administration has aggressively pursued a wide range of restrictive immigration policies. The Administration is attempting to end DACA entirely and some TPS protections, greatly reduce access to refugee and asylum programs, and discourage immigrants’ use of public benefits at the federal level. While a great deal of attention has been focused on President Trump’s proposed U.S.-Mexico border wall, the administration has already substantially altered the immigration landscape through executive actions, rule changes and other more subtle procedural mechanisms. These changes—none of which came in the form of legislation approved by congress—don’t just target unauthorized immigration, but also significantly restrict inflows of immigrants via lawful channels.

In this report, we describe the major immigration program or policy areas that the Trump administration has targeted. For each area, we 1) provide a background description of the program; 2) detail the specific ways the Trump administration has restricted (or attempted/proposed to restrict) the program; and 3) analyze the local impact of these policy changes on people living in Massachusetts. In the final section of this report we summarize key local action areas for better supporting immigrants in Massachusetts. Since it deals with crossing international borders, immigration policy is largely a federal issue. But there are many local opportunities to better support the immigrants who have come to Massachusetts and become part of the fabric of our communities, and we briefly describe some of them in this final section.

DEFERRED ACTION FOR CHILDHOOD ARRIVALS (DACA)

What is DACA and how does it work?

Beginning in 2001, bipartisan groups of legislators began working to create a pathway to citizenship for noncitizen youth brought to the U.S. by their parents as young children—the DREAM Act (the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act). While this legislation never passed into law, the thinking was that undocumented immigrant children, who played no role in deciding to come to the U.S., should not have to live in the shadows in constant fear of deportation. These young people largely grew up in the United States and have been active members of American communities for a significant portion of their lives.

In 2012, after more than a decade of Congressional inaction on the DREAM Act, former President Obama authorized an executive action creating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which provides some DREAM Act–style protections for young immigrants. But because the program was established through executive action, DACA is more limited than many of the DREAM Act proposals. DACA does not offer a path to citizenship (as the DREAM Act would have), but it does provide temporary protection from deportation and access to work permits for formerly unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. who had arrived before the age of 16 and lived in the U.S. for five or more consecutive years.

How has the Trump administration restricted DACA?

As part of a sweeping strategy to restrict immigration to the United States, the Trump administration announced the shuttering of the DACA program in September 2017, at which point U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) stopped accepting new applications. A few months later, a federal court issued an injunction, stating that USCIS must continue accepting renewal applications for current DACA recipients while federal courts determined DACA’s ultimate legality. USCIS is not, however, accepting new DACA applications or providing permission to travel outside the United States to DACA beneficiaries while these legal challenges make their way through the court system. Advocates report that because the U.S. Supreme Court did not take up DACA cases this term, USCIS will likely continue to process DACA renewals until at least October 2019.

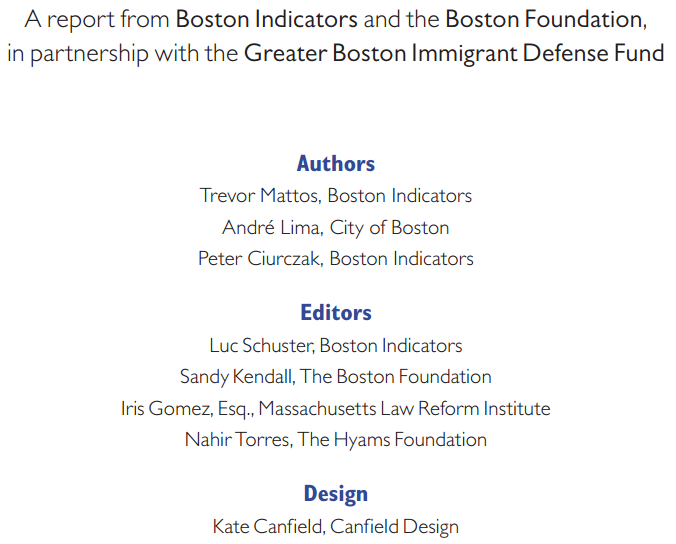

Attempts by the Trump administration to end DACA initially led to a sharp decline in renewals, as shown in Figure 1, although renewal requests have rebounded somewhat following the legal injunction mandating the processing of renewal requests.

Opposition to DACA and proposed legislative solutions for the DACA-eligible population have featured prominently in recent partisan showdowns over the federal budget, including the five-week federal government shutdown during December 2018 and January 2019. While the Trump administration demanded funding for a U.S.-Mexico border wall, some Democratic lawmakers have sought to negotiate permanent protections for DACA grantees either through a compromise with the Trump administration or through separate legislation like the Dream and Promise Act of 2019.4 In the interim, the lives of hundreds of thousands of DACA recipients, who make vital economic and social contributions to Massachusetts and the nation, have been left hanging in the balance.

How are these restrictions being felt in Massachusetts?

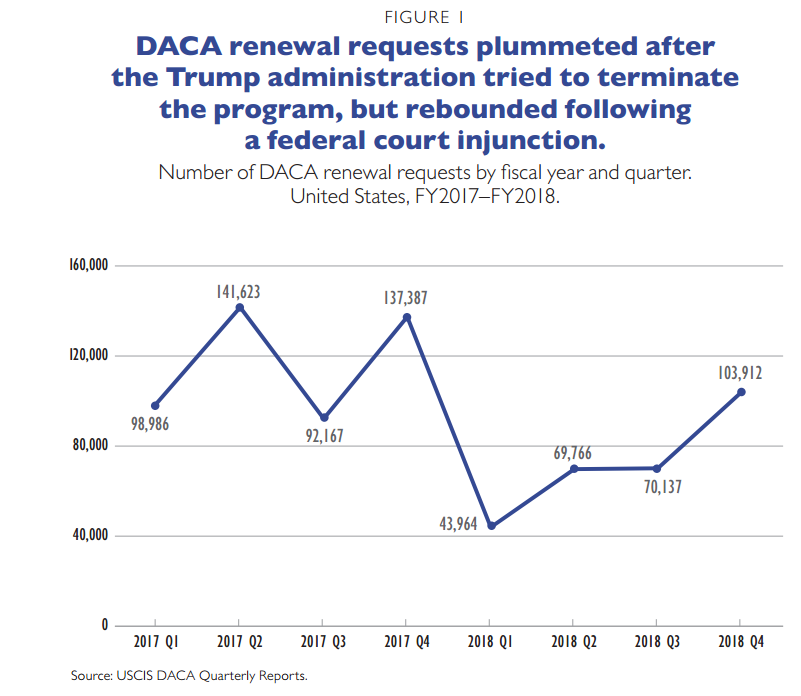

As of September 2018, 823,283 people had received DACA authorization nationwide. In Massachusetts, an estimated 17,000 people likely could qualify for DACA, and so far, 6,030 have applied for and received DACA status. Most of these DACA-eligible people in Massachusetts have roots in Latin America, especially in Guatemala, Brazil and El Salvador.5 Because USCIS has stopped accepting new DACA applications, this means there are roughly 11,000 people in Massachusetts who might still be eligible for DACA status but are waiting in limbo because they cannot currently apply for it. Additionally, those with DACA authorization must anxiously await a final court ruling to determine the future fate of the program upon which they have begun to build their lives.

People with DACA work authorization, like other lawfully authorized immigrants, are able to pay in-state tuition when attending public colleges and universities in Massachusetts if they demonstrate Massachusetts residency. Were DACA to end, these students would face a much more challenging pathway to obtaining a college degree and getting a good job. Students without in-state tuition pay $19,799 more per academic year at UMass Boston and $4,944 more at Bunker Hill Community College each year. Obtaining in-state tuition is especially important for DACA students because they do not qualify for federal financial aid.

TEMPORARY PROTECTED STATUS (TPS)

What is TPS and how does it work?

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) was established in the Immigration Act of 1990 for foreign nationals present in the U.S. from countries in which natural catastrophes or civil conflicts imperil their safe return. TPS recipients can live and work in the U.S. if they cannot return safely to their home country because of natural disaster, armed conflict, or other extraordinary, but temporary, conditions. The Secretary of Homeland Security typically designates TPS for a specific country for 18 months, but protections have often been extended for many years, even decades, if ongoing conditions continue to prevent safe return home. Salvadoran TPS recipients make up 60 percent of the TPS population in the U.S. Only people present in the U.S. before protected status is designated are eligible to remain in the U.S. under the program. TPS recipients may work in the U.S., but are not eligible for most public benefits programs.

How has the Trump administration restricted TPS?

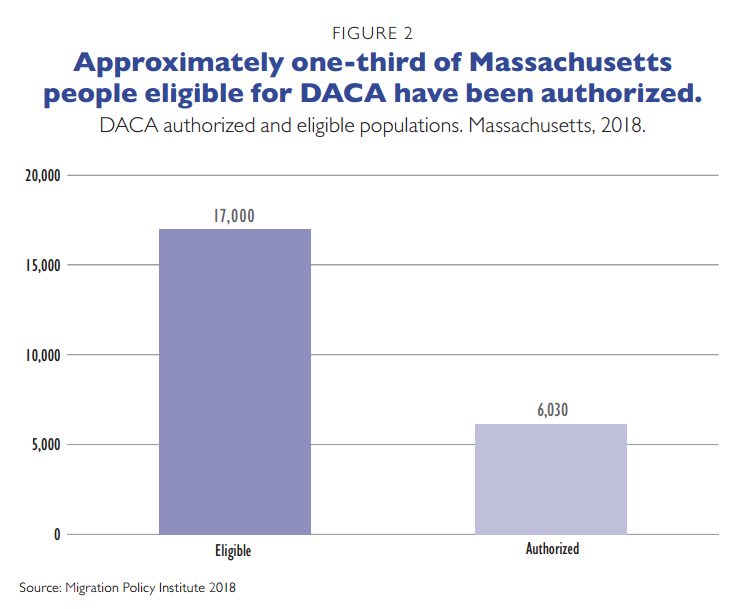

Temporary Protected Status may expire if the conditions in the relevant country have improved sufficiently to allow people to return home. Of the 22 countries designated for TPS since 1990, 12 lost this designation as conditions improved. In more recent cases, legal challenges have prevented some of the terminations, as explained below. This comes largely in response to the Trump administration’s taking a hardline stance on designating and renewing TPS status. Specifically, the administration planned not to renew TPS status for six countries: El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua and Sudan. However, California’s Northern District Court issued a preliminary injunction forcing DHS to keep TPS in place for foreign nationals of four of these countries (see Figure 3), pending resolution of the case. The court found that “TPS beneficiaries and their children indisputably will suffer irreparable harm and great hardship” if they lose TPS,6 adding that local and national economies would suffer if hundreds of thousands of TPS beneficiaries left the U.S. Moreover, the court ruled that the federal government did not demonstrate that any harm would come from maintaining TPS designation pending the outcome of the litigation, and went even further, highlighting plaintiffs’ concerns that the DHS decision to end TPS was “based on animus against non-white, non-European immigrants.” For Haitians, this injunction was buttressed by another injunction entered by a New York federal district court judge in April 2019. TPS holders from Honduras and Nepal who were facing loss of protected status filed a similar lawsuit against the federal government in February 2019. As of March 2019, the court agreed to extend TPS protection for Honduras and Nepal until the Northern District Court resolves its case. Until that time the DHS will automatically extend TPS in nine-month intervals for Honduran and Nepalese TPS holders.7 The administration extended TPS protections for Somalia, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

How are these restrictions being felt in Massachusetts?

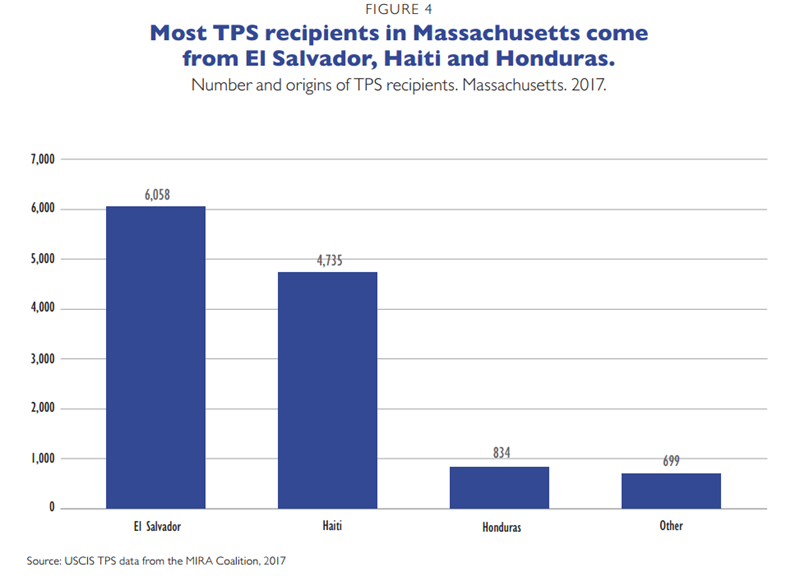

Nationally, there were 436,869 TPS recipients as of November 2017.8 Massachusetts is home to 2.8 percent of them, which is slightly more than the Massachusetts share of the total U.S. population (2.1 percent). Most of the 12,000+ TPS holders in Massachusetts come from El Salvador (6,058), Haiti (4,735) and Honduras (834).9 The ability of these people to stay in the Massachusetts will depend on the outcome of cases currently being heard in federal court. If TPS designations do expire, this will have a measurable, negative impact on the U.S. economy and the Massachusetts economy.10

In an effort to stop the administration from allowing some TPS designations to expire, a coalition of Massachusetts nonprofits has been working on local and national advocacy efforts. Centro Presente, the Massachusetts TPS Committee, the Immigrant Family Services Institute, Haitian-Americans United, and Lawyers for Civil Rights have worked collaboratively to preserve TPS.11 Other Massachusetts-based advocacy groups have been working to preserve TPS protections through letter writing campaigns and outreach to members of the Massachusetts congressional delegation.

HUMANITARIAN PROTECTION PROGRAMS: REFUGEE AND ASYLUM

How do the refugee and asylum programs work?

The United States has a long tradition of welcoming and providing protection to people fleeing violence and persecution in their home countries. This is done through the complementary refugee and asylum programs. The U.S. refugee program works with international partners to process potential refugees located abroad for resettlement in the United States. By contrast, the asylum system offers protection for immigrants who meet the definition of a refugee, but formally request such protection while here in the United States—either at an official U.S. port of entry or from within the U.S. interior. A refugee or asylee is a person who has fled their home country because of past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, membership in a social group, or political opinion.12 As described in the overview of this report, receiving refugee or asylum status in the United States provides many important benefits, like the ability to work and receive state-issued IDs, which allow recipients to become integrated and contribute freely to their communities here in the U.S.

Refugee resettlement procedures are quite complex, involving numerous agencies over a span of 18 to 24 months. The Department of State is responsible for oversight of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP), which has resettled nearly 3.5 million refugees since its inception in 1980.13

Asylum seekers must meet the definition of a refugee and make a claim for asylum protection at the border or within one year of arriving to the U.S. Individuals who may pose danger to the United States are not eligible. There are two routes for asylum seekers: 1) people lawfully present in the United States for less than a year may apply for asylum affirmatively with the Asylum Division of USCIS; 2) people who have entered removal proceedings may apply for asylum defensively in immigration court, as a defense against removal. Immigration courts do not provide legal counsel when immigrants are unable to afford their own. As a result, about 80 percent of immigrants who are detained do not have a lawyer to represent them.14 For asylum seekers, this means vulnerable people are often further burdened with proving they meet the definition of a refugee in court, by providing evidence and testimony. Successfully delivering such testimony is especially difficult because rules of civil procedure for both asylum and removal defense are based on complex legal precedents that are hard for ordinary people to access and these cases do not lend themselves well to self-representation. See the final section of this report for more detail on the importance of legal representation.

Many asylum seekers who make a claim at the border and have no documents permitting entry to the U.S. are processed in expedited removal proceedings.i They are allowed to make their case before an asylum officer if they express fear of persecution. The officer then establishes whether the person has a credible fear of persecution were they to be deported. Asylum seekers who successfully establish credible fear are subsequently referred to an immigration court to proceed with a defensive asylum claim. Unaccompanied minors are not subject to expedited removal.

In the U.S., as throughout the world, asylum claims have increased greatly in recent years due to the civil conflict and instability in many parts of the world. Historically, southern border crossers tended to be individual Mexican migrants seeking work, but over the past two decades a growing number are families and unaccompanied minors fleeing violence in Central America.15

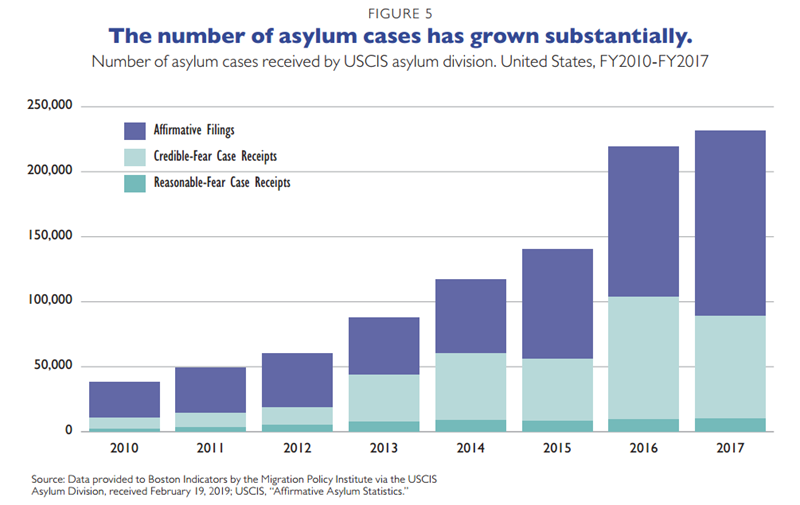

Recently, affirmative asylum requests grew from 27,000 in FY2010 to 143,000 in FY2017 at the USCIS Asylum Division. Unable to process all of each year’s requests, the Asylum Division now has a backlog of 320,000 pending affirmative asylum cases. Most affirmative asylum applicants have waited for two to five years for an interview. Similarly, credible-fear and reasonable-fear cases together expanded from 11,000 in FY2010 to 88,000 in FY2017 (a 700 percent increase).ii In immigration courts, defensive asylum requests now make up 30 percent of the total pending 746,000 cases.16

How has the Trump administration restricted refugee and asylum admissions?

The Trump administration has taken several steps to dramatically restrict refugee and asylum admissions, often citing domestic safety concerns as the main justification. The strategies employed by the administration to restrict refugee and asylum programs have varied but have nevertheless substantially reduced the inflows of refugees. President Trump has directly limited refugee admissions by reducing the annual refugee admissions cap to historically low levels. Additionally, in an effort to reduce successful asylum claims, the administration has produced a host of policy memos and updated official guidance and protocols that work together to narrow eligibility and prevent asylum seekers from ever making a claim for protection in the first place.

REFUGEE RESTRICTIONS

Unlike the asylum system, which gives asylum seekers legal protection once they arrive on U.S. soil, the refugee program is controlled by the executive branch, and so President Trump has been able to simply designate low refugee admissions levels (or, in one case, terminate altogether a special refugee program for Central American minors). The administration has targeted the refugee program by taking the following actions:

Dramatically reducing the annual cap for refugee admissions.

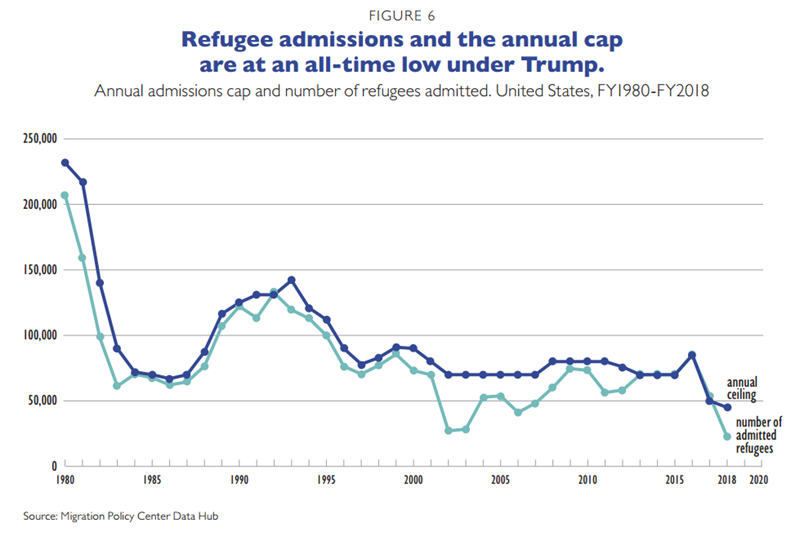

President Trump lowered the annual cap on refugee admissions to 50,000 for FY2017, despite the Obama administration’s having set the FY2017 cap at 110,000. Ultimately, 53,716 refugees entered the U.S. in FY2017. But the Trump administration lowered the cap again for FY2018 to 45,000, the lowest since the establishment of the Refugee Act in 1980. In addition, actual authorized admissions have been reduced even below this annual cap—just 22,491 refugees entered the U.S. during FY2018, another record low since 1980.iii These cap reductions have occurred at the same time that the global refugee population has spiked to nearly 20 million and is now larger than at any other time since 1980.17

Suspending the refugee program for 90 days.

In January 2017, the Trump administration suspended the refugee program by executive order (i.e., the Travel Ban), seeking to completely halt the inflow of foreign nationals from several countries, mostly in the Middle East. This executive action included a full suspension of all refugee admissions, pending a review of security procedures. Although federal courts initially blocked some or all portions of the Travel Ban from going into effect, in June 2018, the Supreme Court upheld a modified version of the Travel Ban that allowed the administration to shut down the Refugee Admissions Program for a review from June 29, 2017, to October 24, 2017.iv

Increasing scrutiny of refugees and family members.

Upon reopening the refugee program on October 24, 2017, the administration implemented new, more restrictive security procedures, including requiring applicants to provide additional information about their personal history. The administration has also required that immediate family members of refugee applicants from 11 high-risk countries complete additional interviews.v These same refugee applicants have received “close scrutiny of potential ties to organized crime,” additional checks that have reduced the efficiency of the program and left would-be refugees and their close family members in danger for extended periods of time.

Ending the Central American Minors (CAM) Refugee Program.

The Trump administration also ended a program that the Obama administration created for Central American minors in 2014, known as the CAM Refugee program. The CAM Refugee program allowed parents lawfully in the United States to request a refugee resettlement interview for their children if they were nationals of El Salvador, Guatemala or Honduras. The program was created in response to a large number of minors fleeing instability in the Northern Triangle of Central America and traveling along dangerous routes through Mexico to find safety in the U.S. The CAM program sought to divert these unaccompanied minors who might have otherwise risked their lives traveling to the U.S.–Mexico border in hopes of claiming asylum. The Department of State stopped accepting new applications for the CAM program in November 2017 and stopped interviewing CAM cases in January 2018. By August 2017 about 1,500 children had arrived in the U.S. under the CAM program, and 2,700 had been conditionally approved for entry when the Trump administration shuttered the program and revoked this preliminary approval.

ASYLUM RESTRICTIONS

As a result of the many procedural changes to how asylum seekers are treated by DHS and USCIS officers, legally established asylum protections have been fundamentally subverted. According to numerous court decisions, the Trump administration has unlawfully attempted to delay or prevent asylum seekers from ever making their claim on U.S. soil. Moreover, recent policy changes have sought to significantly narrow the definition of who is eligible for asylum, and to implement cruel deterrence and detention policies, which have led to multiple deaths of asylum seekers in U.S. custody.18

Thousands of families seeking protection have faced desperate conditions as a result of family separation and policies that have put asylum seekers’ safety at risk while they wait in Mexico. With the relatively dangerous and unstable conditions in Mexican border towns heightened by overcrowding, some migrants awaiting interviews and court hearings in Mexico have suffered from violence and deprivation.19 The Trump administration has effectively sabotaged the humanitarian principles that underlie U.S. and international asylum law designed to protect the world’s most vulnerable people.

Specifically, the Trump administration has worked to dramatically restrict asylum in the U.S. by:

Significantly narrowing the definition of who is eligible for asylum.

In June 2018, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a decision rendering victims of domestic or gang violence, who qualified for asylum under established prior precedent, ineligible for asylum. Then, after 12 victims of violence received negative credible-fear determinations, they brought legal action against former Attorney General Sessions, resulting in a federal judge issuing an injunction that rendered Sessions’ decision on victims of violence unlawful and reversed the credible-fear decision for the 12 plaintiffs.20 However, the denial of asylum to victims of violence in other instances here in Massachusetts and elsewhere did take place nonetheless.21

Subverting asylum seekers’ legal right to claim protection on U.S. soil.

The United States has a longstanding practice of allowing all people fleeing violence or persecution to receive a fair hearing for their claim of asylum safely within the United States.

The Trump administration has undermined asylum law by slowing the pace of processing at official ports of entry in a practice called “metering,” causing many asylum seekers to wait outside of the United States. Immigrants are unable to claim asylum from outside the U.S., and so this has pushed some desperate families to cross the border between ports of entry in order to claim asylum.

In addition, a January 2019 agreement between the Mexican government and the Trump administration established the Migration Protection Protocols, which dictated that asylum seekers (excluding Mexicans and unaccompanied minors) wait for asylum decisions in Mexico, only entering the U.S. for court dates. This was contrary to asylum law, which affords those who enter the U.S. at official ports of entry, or between ports of entry, the right to seek protection and, importantly, to remain in the U.S. while their claim is processed. A federal judge issued a preliminary injunction blocking this policy as of April 2019.

Attempting to implement an asylum ban.

Another harsh tactic the administration implemented was a 90-day “asylum ban,” which began in November 2018. Before it was blocked by the courts, the ban excluded unauthorized border crossers from ever obtaining asylum protection. Such immigrants could, however, obtain temporary protection via a “withholding of removal.”

Separating detained children from their parents (“family separation”).

The Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy established that individuals who cross the border between ports of entry are all to be prosecuted, even first-time offenders. This policy led to separating families and detaining thousands of children separate from their parents, which the administration later reversed after enormous public outcry, electing to detain families together (though notably without the appropriate facilities for such confinement).

Denying bail to asylum seekers apprehended between ports of entry.

In April 2019, Attorney General William Barr directed immigration judges not to allow asylum seekers who cross the border between ports of entry, and are subsequently taken into custody by USCIS, to post bail. The new rule will not apply to children or families.22

How are these restrictions being felt in Massachusetts?

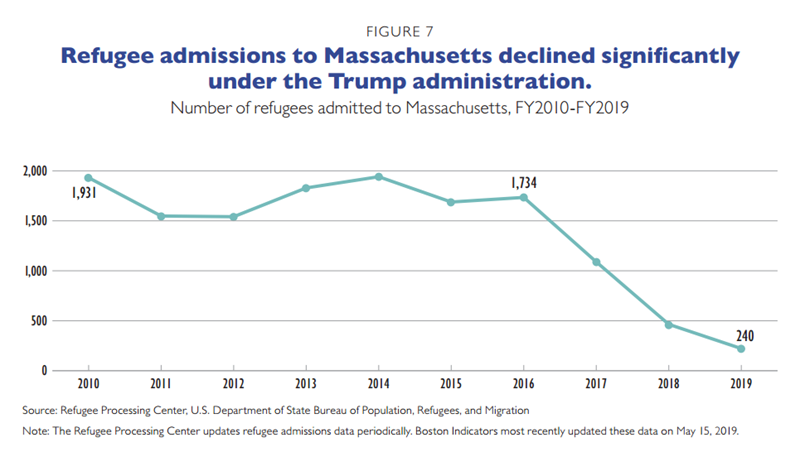

The most recent Massachusetts data on refugees show that the state resettled as many as 1,941 refugees in FY2014, but this number has decreased sharply under the Trump administration. During Trump’s first year in office, Massachusetts refugee admissions fell by nearly 60 percent. Unfortunately, comparable data were not available for asylee admissions to Massachusetts during the years of the Trump administration.

Nevertheless, Massachusetts is a state that welcomes refugees and provides services to help resettle refugee families. For refugees or asylees who are resettled in Massachusetts, the Office for Refugees and Immigrants coordinates a network of organizations that connect refugees to employment services, benefit programs, citizenship and other legal services, translation and ESOL classes. Two such organizations are the Refugee and Immigrant Assistance Center and the International Institute of New England.

i. The 1996 Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) established expedited removal procedures.

ii. The reasonable-fear determination is a special, higher standard for demonstrating the likelihood a person would be persecuted or tortured if returned to their home country. The reasonable-fear standard is used for persons who reentered the U.S. without authorization or were convicted of an aggravated felony. USCIS, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-asylum/asylum/questions-answers-reasonable-fear-screenings

iii. Historically, especially high refugee admissions followed the end of the Vietnam War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when key legislation expanded the refugee program, including the Indochinese Immigration and Refugee Act of 1975, The Refugee Act of 1980, and the 1990 Lautenberg Amendment, which made it easier for some Jewish and Christian people from the former Soviet Union to come to the United States as refugees. USCIS, https://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/our-history/refugee-timeline

iv. To justify their initial decision to suspend and review the program, the administration highlighted cases where noncitizens (including a refugee), or U.S. citizens with ties to allegedly “high-risk” countries (mostly Middle Eastern), had been involved in terrorist plots. In reality, a tiny fraction of refugees admitted to the United States have been implicated in terrorist plots or attacks on U.S. soil. Of nearly 3.5 million refugees admitted to the U.S. since 1975, 20 have been involved in terrorist attacks (less than 1 in 171,000 refugees). Three attacks were deadly, though each of those took place during the 1970s, before more rigorous security protocols were established. Claire Felter and James McBride. How Does the U.S. Refugee System Work? Council on Foreign Relations (accessed March 18, 2019). https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/how-does-us-refugee-system-work

v. Purportedly Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mali, North Korea, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. Migration Policy Institute (accessed February 20, 2019). https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/travel-ban-two-rocky-implementation-settles-deeper-impacts

THE PROPOSED RULE CHANGE FOR "PUBLIC CHARGE"

What is the public charge test for inadmissibility and how does it currently work?

In the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), a longstanding provision disqualifies immigrants from either coming to the United States or obtaining a green card based on a family relationship if they are likely to become primarily dependent on government assistance for income support – to become a “public charge”. In determining whether an immigrant is likely to become a “public charge,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officers and other immigration officials consider whether the person applying to enter the United States or obtain a green card has ever used cash assistance or long-term institutionalized care. These are the primary criteria for inadmissibility. Current law stipulates that immigration officers must consider the totality of an immigrant’s circumstances, including the receipt of such benefits. Apart from cash assistance and institutionalized care, public charge determinations do not currently consider enrollment in programs related to health care, nutrition or housing. In an effort to restrict certain immigrants from entering or remaining permanently in the United States, the Trump administration has proposed sweeping changes to the way immigration officers apply this “public charge” provision.

How has the Trump administration sought to change the public charge test for inadmissibility?

The Trump administration is proposing to significantly increase the number of criteria by which an immigrant may be deemed likely to become a public charge, thereby making someone ineligible to come to or stay in the United States. Rather than assessing whether an immigrant is likely to become primarily dependent on government assistance, the new guidance defines a public charge as anyone who has used any one of many different government assistance programs, including formerly exempt health care, nutrition and housing assistance programs. Also, whereas current practice considers family support a strong factor in the public charge determination, the new rule will assign less importance to affidavits (i.e., guarantees) of family members’ commitment to support the applicant. This proposed rule change comes despite the fact that immigrants pay taxes that help pay for public benefits programs, while being less likely to use those forms of assistance than nonimmigrants.

In fact, were the proposed public charge rule to be applied to U.S. citizens, roughly one third would be unlikely to pass the new test for inadmissibility.23

After DHS published the new draft rule in the federal register, there was a 60-day public comment period during which time the proposed rule received more than 260,000 comments. DHS will have to review these comments before finalizing the new rule in the federal register. Implementation of the rule may take some time and face legal challenges.

While the proposed rule has not gone into effect in the United States, the Department of State has already updated the public charge test in the Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) rules for U.S. consulates abroad, which is applied to “intending immigrants,” individuals applying for visas to move to the United States. The changes to the FAM largely reflect those proposed in the federal register and data already show higher denial rates for visa applicants abroad. For example, there have been recent declines in temporary and immigrant visas approved and a significant spike in the ineligibility findings for immigrant visas (nearly a 40 percent increase between FY2017 and FY2018).24

What impact could changes related to public charge have in Massachusetts?

These public charge rule changes would have far-reaching consequences for particularly vulnerable immigrant communities across the United States, including many noncitizens and their U.S citizen family members who call Massachusetts home. If the proposed rule goes into effect, immigrants who are seeking permanent resident status may be denied more frequently and thus potentially become deportable after having spent years establishing their families in Massachusetts. More deportations would lead to a loss of workers and separation of families. It is also likely that many immigrants would try to avoid these results by discontinuing use of vital government benefits programs like SNAP and MassHealth. This “chilling effect” could negatively impact the health and well-being of entire families, many of which include U.S. citizen children.25

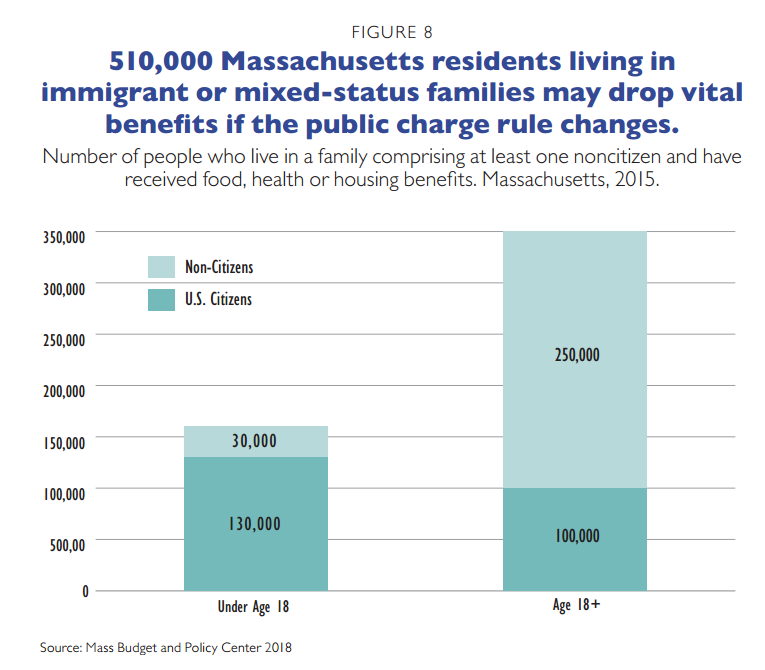

Estimates of the number of households where at least one family member is a noncitizen and one family member has accessed public benefits reveal that as many as 510,000 people in Massachusetts, including 160,000 children, may disenroll from public assistance benefits due to the rule change (see Figure 8). Widespread disenrollment from health insurance or nutrition programs could have a significant, detrimental effect on the health of immigrants and their U.S. citizen family members. One study found that among the state’s Latino population, up to 17,000 U.S. citizen Latino children may drop MassHealth coverage, were the public charge rule implemented.26 The changes to the public charge rule clearly target poorer immigrants, essentially eroding the American Dream. However, Massachusetts organizations like the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy (MIRA) Coalition have encouraged people to submit comments on the proposed rule, which will at least slow the implementation process for DHS.

ADDITIONAL PROCEDURAL RESTRICTIONS ON LEGAL IMMIGRATION

Over the last couple of years, the Trump administration has implemented or proposed dozens of additional procedure and rule changes that work together to systematically obstruct the channels by which immigrants can legally enter and live in the United States. Some of these changes are explored here, ranging from well-known and highly controversial executive actions to lesser-known adjustments in operating protocols that nonetheless have served to dramatically restrict legal immigration.

What has been the impact of the Travel Ban?

The Trump administration issued the first travel ban on January 27, 2017, claiming that the government needed to conduct a thorough review of security procedures and information it received from foreign governments. During the review, the government planned to bar entry for people from seven countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. It also completely suspended the U.S. refugee program for a 120-day review period (discussed previously in this report). In response, eight federal courts issued injunctions that stopped the government from enacting parts of the travel ban, and a week after its initial announcement a federal court in Washington halted the travel ban in its entirety.27

The administration subsequently revised the travel ban twice, eventually limiting the types of travelers that would be blocked from entry. For example, the travel ban ultimately did not include legal permanent residents, dual nationals and refugees scheduled to travel. The countries included in the third and final version (issued in September 2017) were Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela and Yemen. The updated travel ban also included a waiver process for foreign nationals who could meet certain criteria. Federal courts attempted to block the third version of the travel ban, but were overruled by the Supreme Court in June 2018.

The travel ban ended immigrant visas for all banned countries except Venezuela, and banned a variety of nonimmigrant visas such as tourist and business visas for all seven countries. As a result of the travel ban, immigrant visas issued to nationals of Iran, Libya, Syria and Yemen fell by 72 percent and nonimmigrant visas fell by 51 percent between FY2017 and FY2018.28

How have procedural changes been used to restrict worker visas?

For foreign workers seeking to enter or remain in the United States, visa procedures have become more restrictive as well. In accordance with President Trump’s April 2017 executive order related to worker visa processing, the administration has added further steps to limit visas for highly skilled workers. Specifically, DHS will conduct in-person interviews for all employment-based permanent residency applicants. Previously, this only took place if DHS found particular issues with an application. As a result of the now mandatory interviews, more resources are required to process employment-based green card applications, causing family-based immigration and naturalization petitions to be processed more slowly (a stated objective of the Trump administration).29

Federal agencies are rigorously examining employers who hire H-1B and L-1B workers, and no longer allow minimal review procedures for extensions or renewals. During 2017, the administration issued many more denials and requests for evidence (RFEs) than in prior years, including for workers renewing their visas.

Even as administrative rule changes take their toll, more regulatory changes are likely to come, including a ban on H-4 work visas granted to the spouses of H-1B visa holders. DHS submitted a proposed rule change to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in February 2019 that would render dependent spouses of H1-B visa holders ineligible for employment authorization, canceling the H-4 program. After OMB reviews and provides comments on the proposed change, USCIS may revise and submit the proposed rule to the federal register and begin the time for public comment. Finally, USCIS will review comments and then publish the final version of the rule to be implemented (although lawsuits are expected).

How has USCIS made it easier for officers to deny applications, requests and petitions?

In an effort to stall and restrict immigration processing before it even begins, starting in September 2018 USCIS officers who review applications, petitions or requests may choose to deny any such application, petition or request that lacks information or contains any error, without having to first issue a Request for Evidence (RFE) or Notice of Intent to Deny (NOID). Under prior guidance, when an applicant failed to submit a required document or for some other reason USCIS felt the application would not be approved, the decision-making officer would send an RFE or a NOID and allow the applicant an opportunity to provide more evidence. Now USCIS officers may outright deny an applicant without giving the applicant a chance to strengthen their case.30

In practice, greater USCIS officer discretion is especially troublesome when paired with another change to USCIS protocol related to Notices to Appear (NTA)—the charging document that begins deportation cases. Now, not only may immigrants seeking to adjust their status receive a denial without an opportunity to address any questions raised by USCIS concerning their application or eligibility, but on top of that USCIS may now also immediately begin deportation proceedings. Previously, USCIS would consult with ICE beforehand and allow for discretion to be exercised in a humanitarian manner. These two procedural changes together give USCIS adjudicating officers an enormous amount of enforcement power, making it more difficult for immigrants to obtain status, and/or delaying the decision-making process in those cases where the immigrant is allowed to ask the immigration judge to adjudicate the same application.31

What additional actions has the Trump administration taken?

Many other significant changes in immigration processing and enforcement procedures have also come about under President Trump. Some of these include:

- Shifting away from the employer-focused enforcement strategy under former President Obama, ICE has recently expanded worksite enforcement operations and included the prosecution of unauthorized workers as a priority in worksite enforcement strategy.32

- The administration has slowed expedited naturalization for military service members.33

- The administration has developed an intelligence gathering and surveillance apparatus called the National Vetting Enterprise to cull data from social media accounts and other data sources using machine learning and advanced analytics to support immigration enforcement efforts.34

POSSIBLE LOCAL ACTION AREAS FOR BETTER SUPPORTING IMMIGRANTS IN MASSACHUSETTS

Since it deals with crossing international borders, immigration policy is predominantly a federal issue. But once people enter the United States, they lay down roots and become part of local communities. They may periodically interact with federal agencies to renew a visa or apply for citizenship, but most of their interactions are local in nature—buying a home, paying state and local taxes, working, starting a business, attending local schools, using the public library. It is here, at the level of day-to-day life, that Massachusetts and its municipalities can go a long way toward making the immigrant experience a better one. Therefore, we end this report with a brief discussion of ways in which we might better support recent immigrants who are part of our community. This by no means is an exhaustive list. We mention these action areas as one contribution to an ongoing conversation.

We can better support immigrants navigating the legal system.

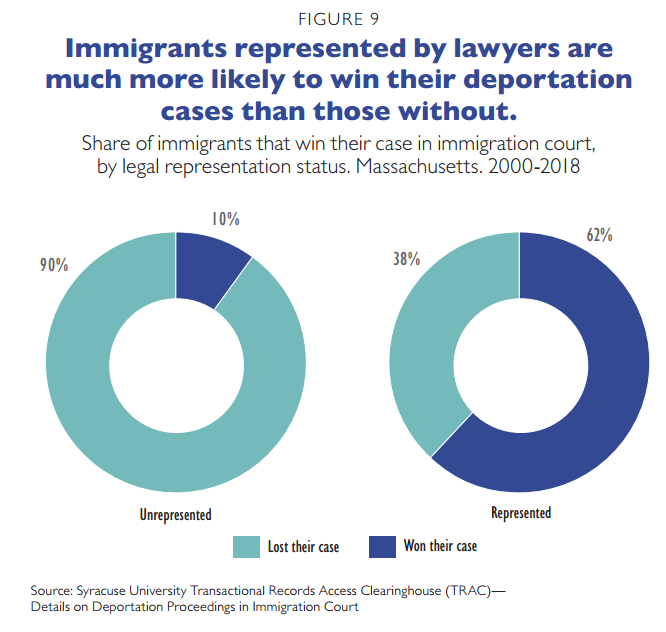

While most immigrants arrive to the United States legally, a subset of these may at some point have to renew or adjust their status (e.g., applying for permanent residency) under changing immigration laws and regulations. For many immigrants, these steps can eventually require an immigration court hearing. However, these courts are civil rather than criminal, and as a result, immigrants appearing before them are not guaranteed a right to counsel—even if they are detained in a county prison such as Suffolk House of Correction or Bristol HOC. Many end up representing themselves in court proceedings that can become very complicated. Better supporting immigrants within the court system is one way of helping people navigate these processes. This is particularly true for immigrants in deportation proceedings, where legal representation often means the difference between deportation and being able to remain in the United States. Immigrants in Massachusetts are six times more likely to win a deportation case if they have legal representation—62 percent win their cases when they have representation compared with 10 percent when they do not.35

To get legal representation to those in need, two legal defense funds have been set up in Greater Boston to fund groups supporting immigrants navigating the court system. The first of these is the Greater Boston Immigrant Defense Fund, a public-private partnership created in 2017 and administered by the Massachusetts Legal Assistance Corporation and coordinated by Massachusetts Law Reform Institute in partnership with the City of Boston and local and national funders. The second is the United Legal Defense Fund for Immigrants, created in 2018 as a public-private partnership between the City of Cambridge and the Cambridge Community Foundation, and expanded in 2019 to include the City of Somerville. Both of these Funds support local organizations that provide representation to individuals in deportation proceedings who are otherwise unable to afford it. These proceedings can be time consuming and expensive, requiring dozens of hours of legal work, with the potential to cost well over $5,000 a case.36 In addition to legal representation, both the Greater Boston Immigrant Defense Fund and United Legal Defense Fund support nonprofits running legal education programs for immigrants such as “know your rights” trainings to prevent detention and deportation, and help immigrants navigate application processes. In the case of the United Legal Defense Fund, this support extends to covering court or other fees. Increasing funding for these partnerships can do much to improve immigrant access to legal services.

We can improve access to education, health care and jobs.

For immigrants currently living here as part of our local communities, there’s much we can do to improve their access to education, health care and jobs. When immigrants participate freely in these aspects of local life, all of us benefit, regardless of immigration status.

ALLOW ALL RESIDENTS WHO HAVE GRADUATED FROM MASSACHUSETTS HIGH SCHOOLS TO PAY IN-STATE TUITION AT OUR PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION.

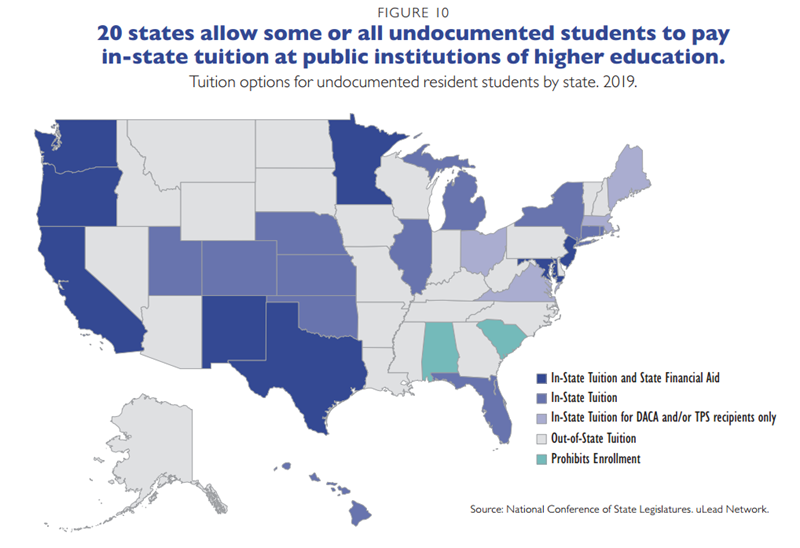

All young people who grew up in Massachusetts and attended our high schools ought to be able to pay in-state tuition when attending public colleges and universities, regardless of immigration status. Yet, currently Massachusetts only allows students holding some form of federal documentation (whether DACA, TPS or some other official status), to pay in-state tuition, even as many other states allow all status and non-status holding students to pay in-state prices. Some states further allow these students access to financial aid, though this is less common. These policies can yield real benefits for students because in-state tuition is often significantly cheaper.37 Extending in-state tuition benefits to all immigrants regardless of status is one way of ensuring that all young people who grew up in Massachusetts can continue their studies.

Our efforts to catalogue how states approach tuition for immigrant youth appear in the map below. These approaches can shift, and there are many nuances across states, so this map offers just a rough picture of major approaches nationwide.

ALLOW ALL CHILDREN TO RECEIVE MASSHEALTH, REGARDLESS OF IMMIGRATION STATUS.

Immigration status can make getting appropriate health care difficult, particularly for low-income children who are not otherwise eligible for MassHealth due to their immigration status. In Massachusetts, 20,000 of these kids have access to only the barest minimums of coverage. Under MassHealth Limited, Health Safety Net and/or the Children’s Medical Security Plan, immigrant children are largely unable to access prescription drugs, emergency care and other services. We could follow the lead of states like California and Oregon by expanding comprehensive MassHealth coverage to all kids regardless of immigration status.38,39

MAKE IT EASIER FOR IMMIGRANTS TO JOIN THE LOCAL WORKFORCE.

Many immigrants to our region were successful professionals in their countries of origin, but joining the American workforce can be a significant hurdle. A 2015 study of immigrant professionals revealed three significant barriers these professionals face to joining their U.S. counterparts:40

- The lack of U.S. work experience.

- Employers didn’t recognize foreign work experience.

- Employers didn’t recognize foreign credentials.

This problem is particularly acute in health care, where more than 20 percent of immigrants with foreign medical credentials are unable to practice in Massachusetts due to “costly licensing requirements, language barriers, lack of targeted career services and other factors.”41 Helping these practitioners gain accreditation in Massachusetts through comprehensive training and language programs, or by modifying license requirements, would ensure that the Commonwealth avoids underutilizing an important, readily available talent resource.

CREATE MUNICIPAL IDS FOR ALL RESIDENTS, REGARDLESS OF IMMIGRATION STATUS.

Municipal IDs have given residents a way to access local services in nearly 20 cities across the United States. These IDs typically allow users to open bank and library accounts, and access other services such as public transit and local discount programs. In many localities, they also operate as valid ID for immigrants, where they are used as proof of residency for law enforcement.

Boston’s own studies of a municipal ID program have suggested there would be significant demand, with a projection of between 257,000 and 347,000 active users.42

ALLOW MASSACHUSETTS RESIDENTS ACCESS TO DRIVER’S LICENSES REGARDLESS OF IMMIGRATION STATUS.

To obtain a license in Massachusetts, residents must either have U.S. citizenship or some form of lawful status or presence. As a result, undocumented immigrants in Massachusetts are not legally allowed to drive within the state. Nevertheless, living in the Commonwealth often requires a car—and expanding driving options for immigrant workers and families is a good way to ensure people make it to work, doctor’s appointments and school on time. In addition to the personal benefits of holding a license, ensuring that all drivers go through the license process improves the safety of the roads overall, as everyone must learn the rules of the road and pass a driving test.

We can better safeguard information sharing with federal immigration authorities.

Despite the countless day-to-day contributions that immigrants make to our communities, they often live in fear that they might be targeted or discriminated against based on their immigration status. Indeed, in some cases, local and state law enforcement, rather than being a supportive presence that helps ensure community safety, can instead be a source of fear for immigrants. Agreements these police departments have with federal immigration authorities may lead to immigrants staying in bad situations (such as with domestic abusers, or employers stealing their wages), out of concern that requesting help could lead to deportation.

LIMIT STATE AND LOCAL PARTICIPATION IN FEDERAL IMMIGRATION MATTERS.

There are a number of ways by which local and state law enforcement can collaborate with federal law enforcement agencies to the detriment of immigrant communities across the United States. When local police are allowed to ask for immigration status, calling the police to report crimes becomes a potentially life-altering decision for immigrants. Of biggest concern are 287(g) agreements, which allow select local and state law enforcement personnel to act as ICE agents. In some cases, this allows agents to shift detainees into ICE custody immediately, bypassing local legal processes entirely. Limiting these local/state-federal law enforcement relationships, as the Safe Communities Act attempts to do, is an important step toward ensuring the safety and security of the state’s immigrant communities.43

Many local and state police departments participate in counterterrorism efforts that include working with their federal counterparts to share information. In order to ensure that immigrants (documented and undocumented) don’t get unnecessarily caught up in federal immigration enforcement, local and state law enforcement agencies could clearly define policies and practices with respect to information sharing. Undocumented immigrants particularly can wind up detained and deported, with little actual due process, as a result of routine information sharing. But these processes don’t have to operate like this. In Providence, Rhode Island, local police are barred from collecting and escalating information to federal authorities without reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. Restoring this community oversight is possible and could be an important way of reining in information sharing agreements.44

ENDNOTES

- Tanvi Misra, “The Cities Refugees Saved,” CityLab, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2019/01/refugee-admissions-resettlement-trump-immigration/580318/

- Wendy Feliz, “Sorry Donald Trump, Immigration Is Still Associated with Less Crime and Safer Communities,” American Immigration Council, accessed April 18, 2019, http://immigrationimpact.com/2016/04/29/donald-trump-immigration-crime-facts/

- Peter Vandor and Nikolaus Franke, “Why Are Immigrants More Entrepreneurial?,” Harvard Business Review, accessed April 18, 2019, https://hbr.org/2016/10/why-are-immigrants-more-entrepreneurial

- Diana Pliego, “Dream and Promise Act: An Important Step Forward for Our Communities,” National Immigration Law Center, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.nilc.org/2019/03/14/dream-and-promise-act-an-important-step-forward/

- Luc Schuster and Anise Vance, “DACA, by the Numbers,” Boston Indicators, accessed April 25, 2019, https://www.bostonindicators.org/article-pages/2017/september/daca-by-the-numbers

- “Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction,” United States District Court Northern District of California, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Laws/ramos-v-nielsen-order-granting-preliminary-injunction-case-18-cv-01554-emc.pdf

- “Bhattarai v. Nielsen: Frequently Asked Questions,” National TPS Alliance, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.nationaltpsalliance.org/bhattarai-lawsuit/bhattarai-faqs/

- Muzaffar Chishti, Jessica Bolter, Sarah Pierce, “Tens of Thousands in Unites States Face Uncertain Future, as Temporary Protected Status Deadlines Loom,” Migration Policy Institute, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/tens-thousands-united-states-face-uncertain-future-temporary-protected-status-deadlines-loom

- “Temporary Protected Status (TPS): An Overview,” MIRA Coalition, accessed April 18, 2019, http://miracoalition.org/images/Documents/TPS-factsheet-update-March14-2019.pdf

- Amanda Baran, Jose Magaña-Salgado, Tom K. Wong, “Economic Contributions by Salvadoran, Honduran, and Haitian TPS Holders,” Immigrant Legal Resource Center, accessed April 24, 2019, https://www.ilrc.org/sites/default/files/resources/2017-04-18_economic_contributions_by_salvadoran_honduran_and_haitian_tps_holders.pdf

- Akilah Johnson, “In Packed Courtroom, Lawyers Spar over Fate of ‘Protected’ Immigrants,” The Boston Globe, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2018/07/12/packed-courtroom-lawyers-spar-over-fate-protected-immigrants/kFBAF5uqeY1u8NkYvwQrGN/story.html

- “An Overview of U.S. Refugee Law and Policy,” American Immigration Council, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/an_overview_of_united_states_refugee_law_and_policy_0.pdf

- Donald Kerwin, “The U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program – A Return to First Principles: How Refugees Help to Define, Strengthen, and Revitalize the United States,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 6(3) 205–225, accessed April 18, 2019, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2331502418787787

- “FAQ About Asylum and the Border,” Human Rights First, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/resource/faq-about-asylum-and-border

- “Statement by Secretary Johnson on Southwest Border Security,” DHS, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2016/10/17/statement-secretary-johnson-southwest-border-security

- Doris Meissner, Faye Hipsman, T. Alexander Aleinikoff, “The U.S. Asylum System in Crisis: Charting a Way Forward,” Migration Policy Institute, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/us-asylum-system-crisis-charting-way-forward

- “Population Statistics,” UNHCR, accessed April 18, 2019, http://popstats.unhcr.org/en/time_series

- Lisa Riordan Seville, Hannah Rappleye, Andrew W. Lehren, “22 Iimmigrants Died in ICE Detention Centers During the Past 2 Years,” NBC News, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/22-immigrants-died-ice-detention-centers-during-past-2-years-n954781

- Carrie Kahn, “Mexican Authorities Arrest 3 Suspects in the Murder of 2 Honduran Teenagers,” NPR, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2018/12/20/678557712/mexican-authorities-arrest-3-suspects-in-the-murder-of-2-honduran-teenagers

- “Grace v. Whitaker – Opinion,” ACLU, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.aclu.org/legal-document/grace-v-whitaker-opinion

- Joel Rose, “As More Migrants Are Denied Asylum, an Abuse Survivor Is Turned Away,” NPR, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/01/18/686466207/its-getting-harder-for-migrants-to-win-asylum-cases-lawyers-say

- Michael D. Shear and Katie Benner, “In New Effort to Deter Migrants, Barr Withholds Bail to Asylum-Seekers,” The Boston Globe, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/nation/2019/04/16/new-effort-deter-migrants-barr-withholds-bail-asylum-seekers/l7J4JfxAuHGeAHI1QaX3lK/story.html

- Danilo Trisi, “One-Third of U.S.-Born Citizens Would Struggle to Meet Standard of Extreme Trump Rule for Immigrants,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/one-third-of-us-born-citizens-would-struggle-to-meet-standard-of-extreme-trump-rule-for

- Stuart Anderson, “New Data Reveal State Department Visa Denials Surged in 2018,” Forbes, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/stuartanderson/2019/03/01/state-department-visa-denials-surged-in-2018/#7bed2cb466d4

- “Impact of Proposed Federal Immigration Rule Changes on Boston: Public Charge Test for Inadmissibility,” Boston Planning & Development Agency, accessed April 23, 2019, http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/e856c564-bf0f-47d4-9a44-75b430903f82

- Fabián Torres-Ardila, Phillip Granberry, Iris Gómez, Vicky Pulos, “The Effect of Proposed Changes in Federal Public Charge Policy on Latino U.S. Citizen Children in Massachusetts,” The Mauricio Gastón Institute for Latino Community Development and Public Policy, accessed April 18, 2019, https://scholarworks.umb.edu/gaston_pubs/230/

- Muzaffar Chishti and Jessica Bolter, “The Travel Ban at Two: Rocky Implementation Settles into Deeper Impacts,” Migration Policy Institute, accessed April 23, 2019, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/travel-ban-two-rocky-implementation-settles-deeper-impacts

- Muzaffar Chishti and Jessica Bolter, “The Travel Ban at Two: Rocky Implementation Settles into Deeper Impacts,” Migration Policy Institute, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/travel-ban-two-rocky-implementation-settles-deeper-impacts

- Muzaffar Chishti, Sarah Pierce, Jessica Bolter, “Even as Congress Remains on Sidelines, the Trump Administration Slows Legal Immigration,” Migration Policy Institute, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/even-congress-remains-sidelines-trump-administration-slows-legal-immigration

- “Policy Memorandum PM-602-0163: Issuance of Certain RFEs and NOIDs; Revisions to Adjudicator’s Field Manual (AFM) Chapter 10.5(a), Chapter 10.5(b),” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Laws/Memoranda/AFM_10_Standards_for_RFEs_and_NOIDs_FINAL2.pdf

- “Policy Memorandum PM-602-0050.1: Updated Guidance for the Referral of Cases and Issuance of Notices to Appear (NTAs) in Cases Involving Inadmissible and Deportable Aliens,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Laws/Memoranda/2018/2018-06-28-PM-602-0050.1-Guidance-for-Referral-of-Cases-and-Issuance-of-NTA.pdf

- Alan Gomez, “Feds Targeting More Worksites Crack Down on Undocumented Workers – But Not Their Employers,” USA Today, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2018/12/11/donald-trump-targeted-more-worksites-undocumented-immigrants-immigration-and-customs-enforcement/2263656002/

- “Changes to the Expedited Naturalization Process for Military Service Members,” National Immigration Forum, accessed April 29, 2019, https://immigrationforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/changes_expedited_natz_process_military-20180329.pdf

- Chinmayi Sharma, “The National Vetting Enterprise: Artificial Intelligence and Immigration Enforcement,” Lawfare, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.lawfareblog.com/national-vetting-enterprise-artificial-intelligence-and-immigration-enforcement

- Details on Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court, Syracuse University Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), accessed April 5, 2019, https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/nta/

- United Legal Defense Fund – Cambridge Community Foundation, http://cambridgecf.org/united-legal-defense-fund-for-immigrants/

- Luc Schuster and Anise Vance, “DACA, by the Numbers,” Boston Indicators, accessed April 5, 2019, https://www.bostonindicators.org/article-pages/2017/september/daca-by-the-numbers

- “Expand Health Coverage for Children,” Health Care for All, 2019-2020 Priority Legislation, accessed April 5, 2019, https://www.hcfama.org/blog/health-care-all-2019-2020-legislative-priorities

- “Sen. DiDomenico Attends MIRA Events,” Chelsea Record, accessed April 5, 2019, http://chelsearecord.com/2019/03/22/sen-didomenico-attends-mira-events/

- “Barriers to Work: Improving Access to Licensed Occupations for Immigrants with Work Authorization,” National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed April 5, 2019, http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/barriers-to-work-immigrants-with-work-authorization.aspx

- “Foreign-Trained Doctors, Nurses Seek to Reduce Barriers to Practice,” Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, accessed April 5, 2019, http://miracoalition.org/news/746-foreign-trained-doctors-nurses-seek-to-reduce-barriers-to-practice

- Municipal ID Feasibility Study, City of Boston, accessed April 5, 2019, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B90zSlEnMz_zMHZfNGR0VGF2dGJzRHZ4YU4yd1gzdFZtVVBV/view

- Danyelle Soloman, Tom Jawetz, Sanam Malik, “The Negative Consequences of Entangling Local Policing and Immigration Enforcement,” Center for American Progress, accessed April 5, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/reports/2017/03/21/428776/negative-consequences-entangling-local-policing-immigration-enforcement/

- Kade Crockford, “Beyond Sanctuary: Local Strategies for Defending Civil Liberties,” The Century Foundation, accessed April 5, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/beyond-sanctuary/