Nationwide and in Massachusetts, the LGBT community has won key legislative victories, built impactful institutions, and nurtured cultures of resilience and support. Today, the LGBT community faces different challenges than it did a generation ago. Yet the same determination, creativity and collaboration that was so effectively used to produce positive change in decades past will be required to address today’s issues. In this report, we highlight four groups with pressing concerns and a cross-cutting topic that affects the entire LGBT population:

- LGBT youth;

- LGBT youth of color;

- The transgender community;

- LGBT older adults;

- Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data collection.

LGBT YOUTH

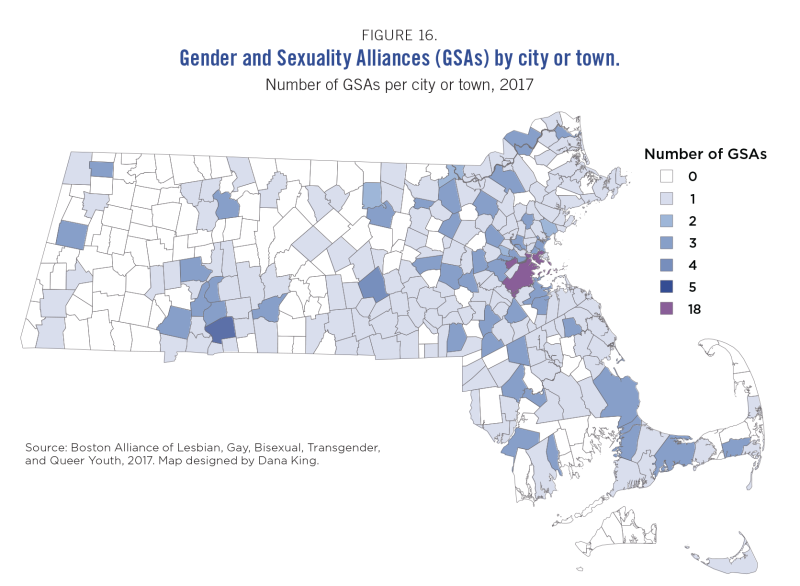

Massachusetts has relatively robust, high-quality supports for LGBT youth. Local resources that contribute to the network of support for LGBT youth include: Gender and Sexuality Alliances (GSAs), Alliances for GLBT Youth (AGLYs), the Safe Schools Program for LGBTQ youth, and the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth.

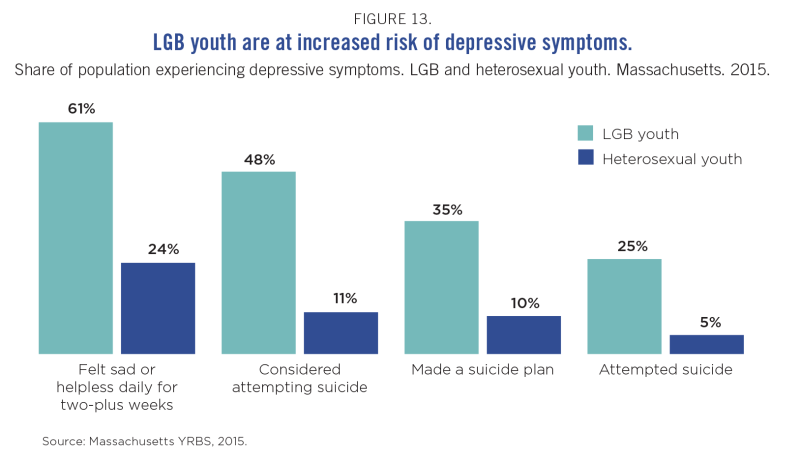

Even so, LGBT youth continue to face a significant burden of mental health challenges. In Massachusetts in 2015, more than half of all LGB youth reported feeling so sad or helpless that they stopped doing some of their usual activities. Almost half considered attempting suicide, more than one-third made a suicide plan, and one-quarter attempted suicide. Each of these statistics was more than double the corresponding number for heterosexual youth.49

Numerous factors likely contribute to the severe symptoms of depression reported by LGB youth in Massachusetts. Among them is the degree to which LGB youth are bullied, threatened and/or injured at school. Statewide, 13.4 percent of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) youth did not attend school in 2015 because of safety concerns.50 Nationally, LGB youth report being threatened or injured with a weapon on school property at almost twice the rate of heterosexual youth—10.0 percent and 6.7 percent, respectively.51

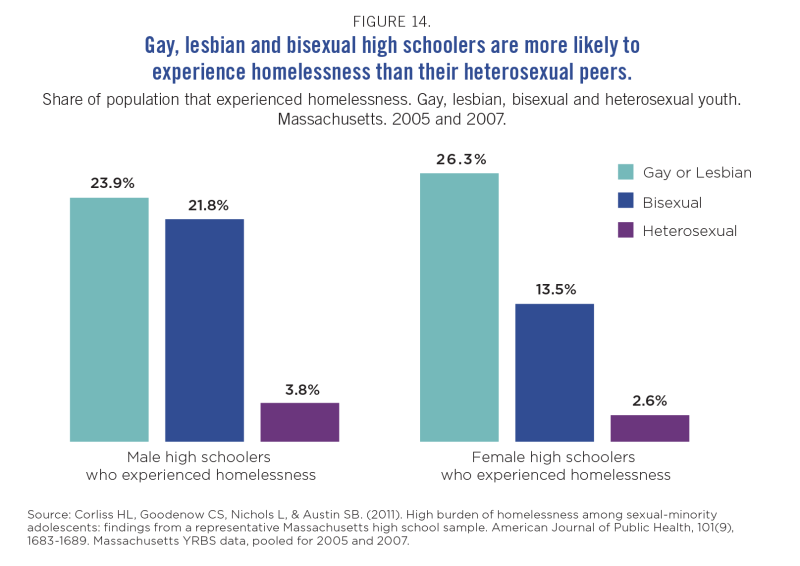

Widespread homelessness is another factor that likely contributes to the high rates of depression reported by LGB youth. One in four gay or lesbian high schoolers have been homeless at some point, while less than one in 20 heterosexual high schoolers in Massachusetts have experienced homelessness.52 These disparities in the sexual orientation of homeless youth are driven in part by family relationships, which can often lead to LGBT youth running away from home or being thrown out of their homes.

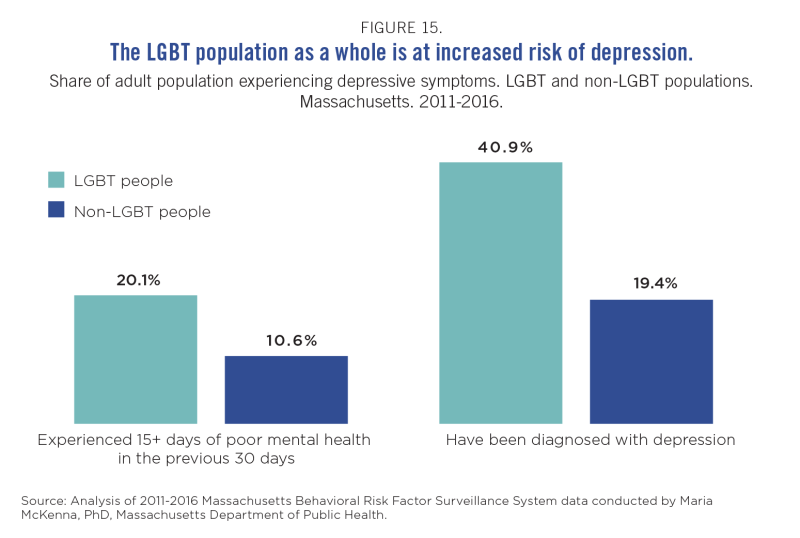

Often living under highly stressful conditions, LGBT youth struggle with mental well-being—and, it should be noted, so does the LGBT population more broadly. According to an analysis of pooled Massachusetts BRFSS data from 2011 to 2016, 20.4 percent of LGBT adults experienced 15 or more poor mental health days in the past month, and 38.8 percent had, at some point, received a depression diagnosis. The corresponding figures for non-LGBT people were 10.5 percent and 19.1 percent, respectively.53

How Can We Support LGBT Youth?

There are a number of exemplary programs, organizations and policies in Massachusetts that should be highlighted, funded and promoted throughout the state. Additionally, model programs and policies from other parts of the country should be replicated locally.

Please note that the list below is far from exhaustive; rather, it is a starting point for ongoing conversations about ideas for action.

- PROGRAMS THAT SUPPORT THE MENTAL AND EMOTIONAL HEALTH OF LGBT YOUTH:

- Alliances for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Youth (AGLYs) are social support organizations that connect LGBTQ youth to both services and one another. AGLYs are particularly important to LGBT youth who live in places with fewer resources than Boston, such as the North Shore or western Massachusetts. AGLYs subsist on limited budgets, and often staff are very part-time and underpaid. More resources from funders could allow for the strengthening of Massachusetts’ extensive AGLY network.

- Camp Aranu’tiq is the first-ever summer camp established for transgender and gender-variant/gender nonconforming youth. The camp seeks to build confidence, resilience and community for transgender and gender variant youth and their families. Camp Aranu’tiq is headquartered in Needham, Massachusetts, and the camp is located in New Hampshire.

- PROGRAMS AND TRAININGS THAT HELP PROTECT LGBT YOUTH AT SCHOOL:

- Safe schools programs, Gender Sexuality Alliances in schools and competency training of school staff all contribute to a safer and more welcoming educational environment for LGBT youth. These programs and trainings should be further expanded upon in the locales where they currently operate, and should be extended to areas where they do not.

- PROGRAMS THAT ADDRESS HOUSING AND HOMELESSNESS:

- Y2Y Harvard Square, a student-run overnight shelter, provides a safe and affirming environment with gender neutral spaces for young adults experiencing homelessness. While Y2Y is highly successful, it does not have the capacity to meet the need for housing among LGBT homeless youth. Also, it is closed for several months each year. Replicating the Y2Y model on a larger scale and for 365 days a year is needed.

- PROGRAMS AIMED AT NURTURING FAMILY ACCEPTANCE:

- The Family Acceptance Project (FAP), based at San Francisco State University, is “a research, intervention, education and policy initiative” that emphasizes the importance of family acceptance of LGBT youth.54 It aims to prevent health and mental health risks for LGBT youth—including suicide, homelessness and HIV—in the context of their families, diverse cultures and faith communities. FAP has had success in nurturing support from parents in conservative faith communities, thus reducing the vulnerability of LGBT youth to behavioral health concerns, homelessness and other issues.

LGBT YOUTH OF COLOR

As part of the LGBT youth population, youth of color confront some challenges that are the same as the general LGBT youth population and other challenges that are distinct.

A significant share of the LGBTQ youth of color population struggles with difficult and compounding economic and living circumstances.

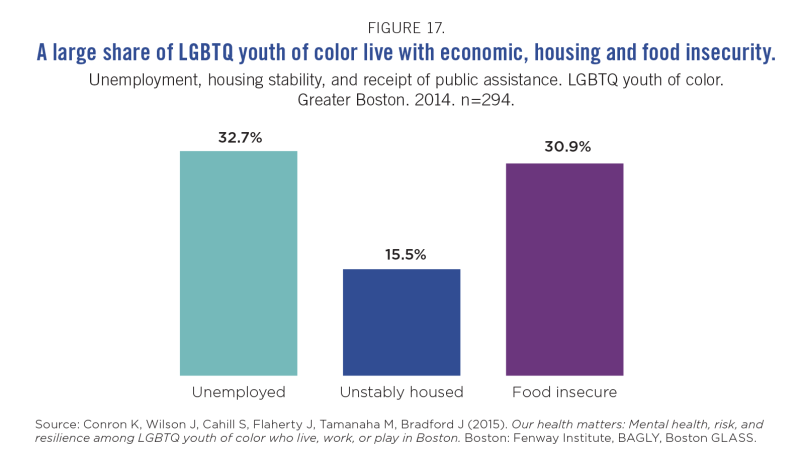

A 2014 study of LGBTQ youth of color in Greater Boston found that one-third (32.7 percent) were unemployed, 15.5 percent were unstably housed, and 30.7 percent were food insecure. In an attempt to meet their needs, over half (52.6 percent) reported receiving public benefits/ government assistance, such as MassHealth insurance or food stamps. Still, a great deal of need is not being met and many LGBTQ youth are forced to extreme lengths to survive. Some 15.7 percent reported exchanging sex for a place to sleep, money, food, drugs or other resources in the prior three months.55

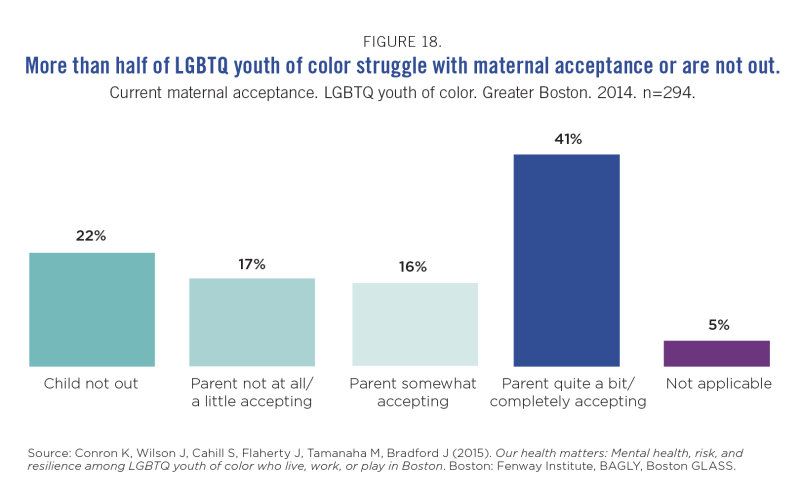

Familial acceptance is likely another contributing factor to the mental health challenges LGBTQ youth of color face. More than half of LGBTQ youth of color, and many LGB youth broadly, continue to struggle with maternal acceptance or are not out. There is a clear link between parental rejecting behaviors and negative health outcomes in lesbian, gay and bisexual young adults.56

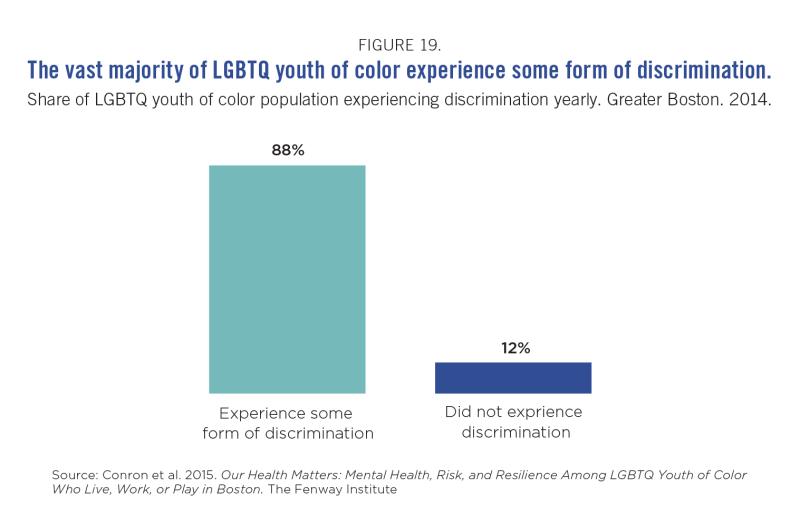

Living at the intersection of multiple identities that are often marginalized, LGBTQ youth of color also experience widespread discrimination. In Greater Boston, nearly 90 percent of the 294 LGBTQ youth of color surveyed in 2014 reported experiencing discrimination based on one of their demographic characteristics (e.g. race, sexual orientation, gender). In other words, discrimination is a near-universal experience for LGBT youth of color.

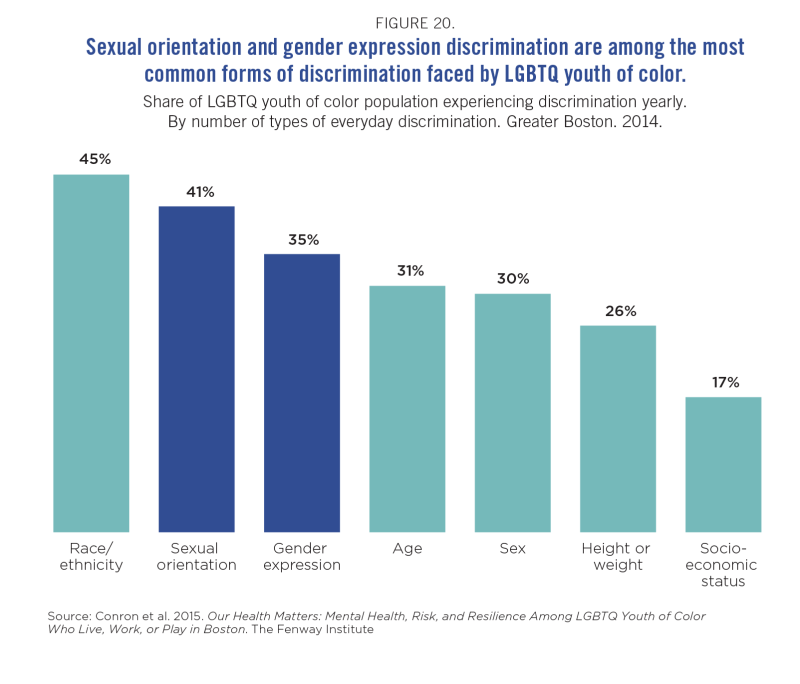

Among LGBTQ youth of color, the most common basis for experiences of discrimination was race/ethnicity (44.6 percent). Sexual orientation (41.2 percent) and gender expression (35 percent) were the second and third most common bases.

LGBT youth of color also live under the threat of hate-based violence, an extreme form of discrimination. Fear of suffering attacks is, without question, warranted: In 2014, 60 percent of LGBTQviii survivors of reported hate-based violence were people of color, as were half of the LGBTQ victims of reported hate-based homicides.57

Given the myriad and severe difficulties they confront daily, it is not surprising that LGBT youth of color are at a high risk of developing depressive symptoms. Among a sample of LGBTQ youth of color in Greater Boston, 40 percent reported symptoms of depression/anxiety and 20 percent reported having attempted suicide.58

How Can We Support LGBT Youth of Color?

There are a number of exemplary programs, organizations and policies in Massachusetts that should be highlighted, funded and promoted throughout the state. Additionally, model programs and policies from other parts of the country should be replicated locally.

Please note that the list below is far from exhaustive; rather it is a starting point for ongoing conversations about ideas for action.

- PROGRAMS THAT PROVIDE SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL SUPPORT:

- The Boston House and Ball Community is a mostly Black gay and transgender community that provides social support. Rooted in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, and possibly dating back to the Civil War era,59 the House and Ball Community has since grown into an extensive support network, spanning multiple cities across the United States.60 The community includes “Houses,” which function somewhat like gender diverse sororities or fraternities, directed by a house “mother” and “father.” Organizers convene “Balls,” which are elaborate events that include voguing and runway competitions performed in drag or in creative costumes.”61 The House and Ball Community provides a supportive space for many LGBT youth whomay be marginalized due to racism, poverty, anti-LGBT prejudice, and rigid gender norms.62

- TRAININGS AIMED AT BUILDING CAPACITY IN SERVICE PROVIDERS:

- The challenges faced by LGBT youth of color often relate to race, sexual orientation, gender identity or some combination of these identities. Understanding issues of intersectionality and the experiences unique to it are crucial for providing LGBT youth of color with the supports they need. Trainings and educational workshops on intersectionality are, then, highly important opportunities to build service providers’ capacities to assist LGBT youth of color.

THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY

LGBT people experience pervasive discrimination: one in four LGBT people nationwide reported experiencing discrimination in 2016.63 LGBT people experience unfair treatment in employment,64 housing65 and public accommodations.66 They also experience prejudice in health care,67, 68 which can become a barrier to necessary medical services. Even if individuals have not experienced it themselves, reports of discrimination against community members can discourage LGBT people from accessing care.

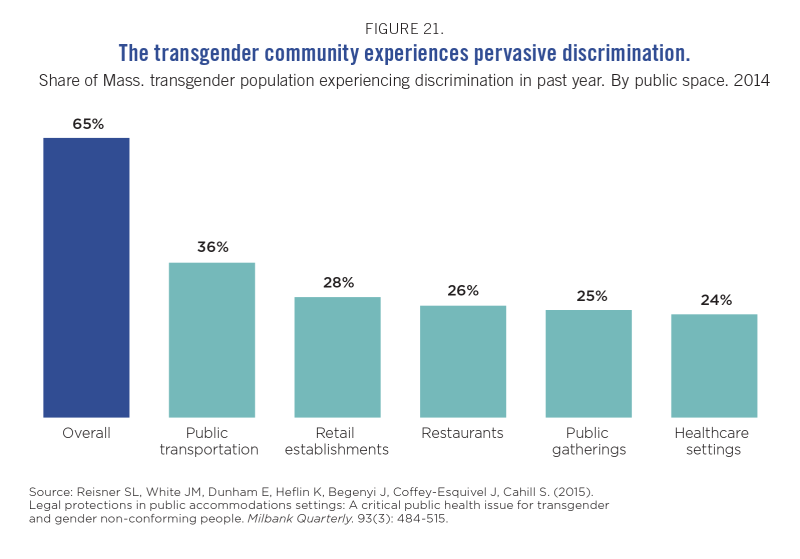

Transgender people are especially affected by discrimination. A 2014 study by the Fenway Institute and the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition found that 65 percent of transgender Massachusetts residents experienced discrimination in public spaces in the past 12 months. The most common setting in which discrimination occurred was public transportation, but no setting was immune to it.

Transgender people also receive differential treatment when seeking housing. Some 61 percent of transgender people experienced housing discrimination, including receiving quotes for higher rental prices and fewer financial incentives than their cisgender peers, in a 2017 study conducted by Suffolk University Law School.69

Even more disturbing is the degree to which transgender people are at risk of violence. In 2014, two-thirds of the LGBTQix victims of hate-based homicides were transgender, despite transgender people accounting for a small numeric share of the entire LGBT population.70

The effects of anti-transgender discrimination are multiple and profound. From education to employment,71 from housing to health care,72, 73 from physical safety to mental health, discrimination can touch every facet of a transgender person’s life. Many of these effects are further compounded by the economic hardship experienced by transgender people. In Massachusetts, a greater share of transgender people are unemployed (7 percent) than cisgender people (4.8 percent). A greater share of transgender people are also living in poverty (17 percent) than cisgender people (11.5 percent).

How Can We Support The Transgender Community?

There are a number of exemplary programs, organizations and policies in Massachusetts that should be highlighted, funded and promoted throughout the state. Additionally, model programs and policies from other parts of the country should be replicated locally.

Please note that the list below is far from exhaustive; rather it is a starting point for ongoing conversations about ideas for action.

- PROGRAMS AND TRAININGS THAT COULD HELP PROTECT TRANSGENDER PEOPLE FROM DISCRIMINATION:

- Providing comprehensive competency training for social service and health care providers who might serve transgender people is critical to avoiding behaviors ranging from insensitive to discriminatory.

- Public awareness and education campaigns should be created to inform the public about the extent of anti-transgender discrimination in public accommodations and the importance of nondiscrimination law as a recourse for transgender people.

- ORGANIZATIONS THAT ADVOCATE FOR AND SERVE THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY:

- Supporting organizations that advocate for the advancement and rights of transgender people is integral to the health and representation of the community at large.

- POLICIES THAT COULD HELP SUPPORT THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY:

- Introducing non-binary gender markers on state identity documents, such as drivers’ licenses, to include individuals who identify as gender non-binary would be a significant step forward. According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality, 36 percent of nearly 28,000 transgender respondents identified as non-binary.74

- Defending the gender identity nondiscrimination law on the November 2018 ballot referendum is crucial to ensuring equal treatment of transgender people in public spaces. (For more, see the detail box, below)

|

|

The 2018 Ballot Question on Public AccommodationsIn 2016, Massachusetts passed a public accommodations law which aimed at curtailing discrimination against transgender people in public spaces. A referendum to overturn this law will be on the November 2018 ballot in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Transgender Anti- Discrimination Veto Referendum asks residents to respond to the question: “Do you approve of a law summarized below, which was approved by the House of Representatives by a vote of 117-36 on July 7, 2016, and approved by the Senate by a voice vote on July 7, 2016?”75 Individuals who vote “yes” will be voting in favor of upholding gender identity nondiscrimination in public accommodations, while those who vote “no” will cast a vote in favor of repealing the 2016 public accommodations law. Freedom Massachusetts is leading the “yes” vote campaign, while Keep MA Safe is leading the “no” vote campaign, the latter arguing that the gender identity nondiscrimination law threatens the safety of women and children in public restrooms. The majority of the funding backing the “no” vote campaign comes from the Massachusetts Family Institute, “a proactive, public voice on a number of issues including: strengthening, protecting, and preserving marriage between a man and a woman.”76 The Massachusetts Family Institute is a state affiliate of Focus on the Family, the largest Christian right advocacy group in the U.S.77 Focus on the Family’s political agenda includes banning abortion, opposing sexual health education and opposing legal equality for LGBT people.78 The campaign against transgender nondiscrimination legislation often misrepresents the transgender community in a way that is harmful and stigmatizing. These representations, in the form of advertisements and TV commercials, can take a significant emotional toll on transgender individuals. Even if the veto referendum to repeal gender identity nondiscrimination in public accommodations is defeated in November 2018, those serving, educating and providing care to the transgender community should take into consideration the emotional impact, particularly on transgender youth, of exposure to and fighting against such injurious misrepresentations. If the veto referendum overturns transgender protections in public accommodations, Massachusetts would become the first state in the nation to do so. Because the Commonwealth has a longstanding reputation as a leader in LGBT rights and progressive causes more generally, reversing these protections would set a dangerous precedent for the entire country.

|

|

LGBT OLDER ADULTS

Older adults who grew up in the 1940s and 1950s came of age in an environment in which heterosexism, homophobia and stigmatization were far more powerful and less challenged than they are today.79 Growing up among these prejudices is likely a driving cause behind the much lower rates of older residents identifying as LGBT—2.7 percent for 65 to 74 year olds as compared to 15.5 percent for 18 to 24 year olds (see Figure 2 at the beginning of this report).

Today, older LGBT adults, many of whom were trailblazers in securing the LGBT community’s landmark victories, are often isolated from the supports they need. Services and social networks are more concentrated in urban areas—places where many LGBT older adults cannot afford to live.

The geographic isolation of older LGBT adults is deepened by several demographic trends. Older LGBT adults are more likely to report being physically disabled or have poor mental health outcomes compared to the general population.80 Caregiving often becomes the responsibility of family members, typically the children of the aged person. However, older LGBT adults are three to four times less likely to have children, and more likely to be single and living alone in their old age, as compared to their heterosexual peers.81

Older gay men are at particular risk of isolation as they are less likely than lesbians to have children82 and have lost significant friendship networks to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.83 Moreover, older gay and bisexual men are at the intersection of two populations that are highly vulnerable to HIV: 65 percent of people living with HIV in the Commonwealth are age 50 or older84 and, in 2014, 46 percent of new HIV infections in Massachusetts were diagnosed in men who have sex with men.85

Lesbian and bisexual women also face significant health challenges. They experience cervical cancer at the same rate as heterosexual women but are less likely to get routine preventive screenings for cervical cancer.86 They may be at higher risk for breast and ovarian cancer related to higher rates of nulliparity (never having given birth), higher rates of obesity and lower rates of mammograms.87

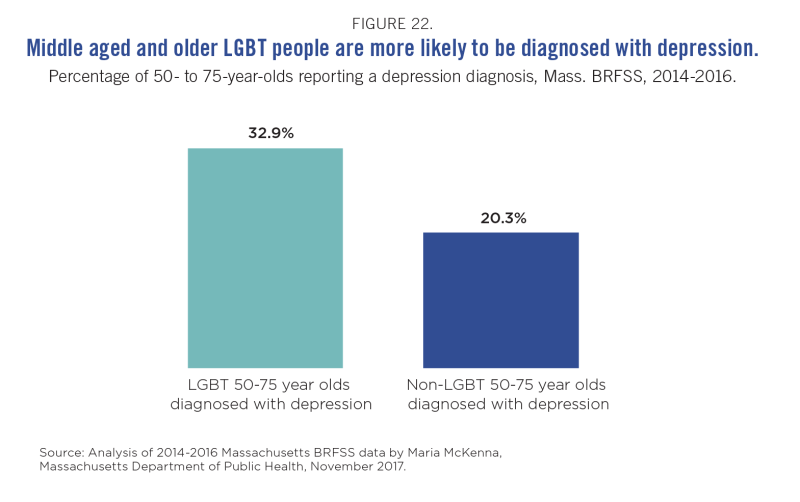

Given the isolation and health challenges they experience, it is no surprise that one in three LGBT adults age 50 to 75 has been, at some point, diagnosed with depression. By comparison, one in five non-LGBT elders has been diagnosed with depression.88

Despite crucial health challenges, many older LGBT adults are not well connected to elder services. Many experience prejudicial treatment from heterosexual age peers or from service providers, or fear they will experience such treatment based on past experiences of discrimination.89 LGBT older adults may, then, be less likely than their non-LGBT peers to access senior centers and congregate meal programs or seek housing assistance, food stamps or other supports.90

How Can We Support Older LGBT Adults?

There are a number of exemplary programs, organizations and policies in Massachusetts that should be highlighted, funded and promoted throughout the state. Additionally, model programs and policies from other parts of the country should be replicated locally.

Please note that the list below is far from exhaustive; rather it is a starting point for ongoing conversations about ideas for action.

- PROGRAMS THAT PROVIDE SOCIAL SUPPORT:

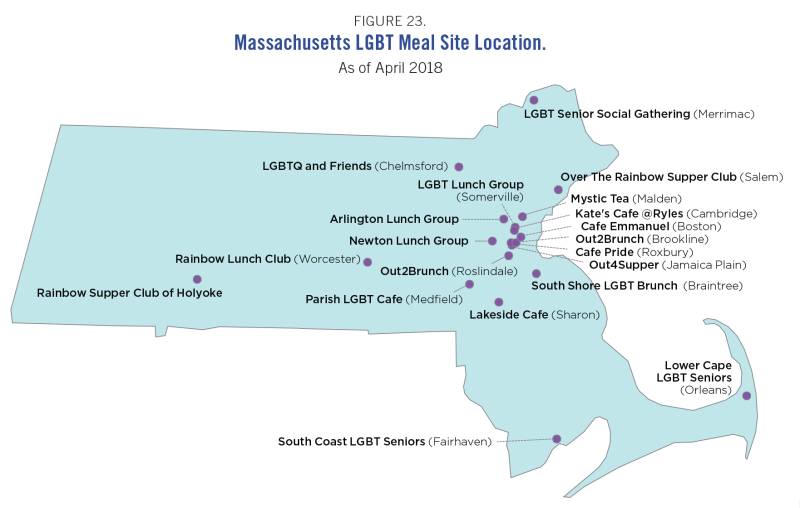

- Congregate meal programs for LGBT elders and their friends can help them develop, strengthen and sustain social support networks. Massachusetts has more congregate meal programs, funded by the Older Americans Act, for LGBT elders and their friends (20) than the rest of the nation combined.91 The LGBT Aging Project helped launch many of these meal programs. A 2012 study of LGB elders who attended LGBT-friendly congregate meal programs in Massachusetts found that they traveled much farther than heterosexual elders who attended mainstream Older Americans Act-funded meal programs.92 Some traveled 50 miles or more to see friends once a month, indicating the need for congregate meal programs in more communities.

- Programs such as the Beacon Hill Village Project and JP at Home provide social events, programming and information, and referrals to vetted providers of home care and maintenance services for older adults.

- LGBT-friendly older adult visitor programs that match younger people to LGBT elders also provide support and reduce social isolation. Ethos in Jamaica Plain, an Aging Service Access Point (ASAP), runs such a program, as does Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE) in New York City.

- PROGRAMS THAT PROVIDE ACCESS TO EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMMING AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT FOR OLDER LGBT ADULTS:

- Old Lesbians Organizing for Change (OLOC) provides members with a community united in a common mission of confronting ageism, sharing mutual interests, and experiencing the joy and warmth of playing and working together.

- Rainbow Lifelong Learning Institute Boston offers LGBT older adults and their friends the opportunity to build and strengthen community through educational programs and social activities.

- TRAININGS AND POLICIES THAT WOULD BENEFIT OLDER LGBT ADULTS:

- Cultural competency training of elder care workers and home care aides in issues affecting LGBT older adults has been shown to improve older LGBT adults’ experiences in mainstream senior service settings.93 This training should be a core component of the overall education provided to those who care for older adults.

- The Massachusetts Executive Office of Elder Affairs (EOEA) started collecting sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data from elders accessing services in 2016 to understand whether LGBT older adults experience any barriers to accessing these services. EOEA should report data findings to improve elder services. All providers of care and services to older adults should collect voluntary, confidential SOGI data, along with other demographic data, to ensure that LGBT older adults are accessing the services they need.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER IDENTITY (SOGI) DATA COLLECTION

Federal SOGI Data Collection and Context

The collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data is important to better understand the experiences of LGBT people, the extent to which they are accessing social services and the disparities affecting them. SOGI data can be collected on population-level surveys, as well as in social services and in health care settings.

For decades now, researchers and activists have promoted adding SOGI questions to federal surveys to capture health and demographic data about LGBT people. Under the Obama Administration, the number of federal surveys that included sexual orientation questions increased to twelve, seven of which also included questions about gender identity or transgender status.94 Among the federal surveys that include SOGI questions are:

- The Health Center Patient Survey,

- The National Adult Tobacco Survey,

- The Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health,

- The National Crime Victimization Survey, which collects data on intimate partner violence,95

- The National Inmate Survey, which collects data on sexual assault in prison as mandated by the Prison Rape Elimination Act.96

Federal surveys collecting sexual orientation data but not gender identity data include:

- The National Health Interview Survey,

- The National Survey on Drug Use and Health,

- The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, and

- The National Survey of Family Growth

Unfortunately, the forward momentum on adding SOGI questions to surveys appears to have slowed, and even stopped, under the Trump Administration. In 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services proposed eliminating the National Survey of Older American Act Participants survey question on sexual orientation and a follow-up question on transgender status, and reversed plans to add SOGI questions to a disability survey administered by the Administration for Community Living.97 The National Survey of Older Americans Act Participants collects data on participation in Older Americans Act- funded services and programs, such as home care assistance and congregate meal programs. In response to community push-back, the sexual orientation question was added back to the OAA survey, but not the transgender status question. SOGI questions remain excluded from the disability survey.

As this report went to press, the U.S. Department of Justice published plans to remove SOGI questions from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) for 16 and 17 year olds “due to concerns about the potential sensitivity of these questions for adolescents.”98 Collecting such data is important in understanding whether or not LGBT people experience disproportionate violent crime. We know from other studies that lesbian and bisexual women, and bisexual men, experience higher rates of intimate partner violence, which is also documented in the NCVS.99

In order to continue making progress in understanding LGBT health and the structural determinants affecting the health of LGBT people, we must resist these rollbacks. Education and advocacy, such as submitting public comment opposing the removal of SOGI questions from federal surveys, are two important levers in that effort. Additionally, Massachusetts’ civic and political leaders should push for continued and expanded SOGI data collection by our federal government.

State and Local SOGI Data Collection

REPORTING ON AND MAKING AVAILABLE EXISTING DATA

As noted earlier in this report, Massachusetts has been a national, and even global, leader in adding SOGI data collection questions to surveys. Many state and local surveys in the Commonwealth, such as the Youth Risk and Behavioral Risk Factor surveys, already collect SOGI data.x

Yet while this data has been collected for several years, there is a lack of regular publication and reporting of it by state agencies. Given the increasing diversity of the LGBT community in Massachusetts, analysis is needed at the intersections between LGBT respondents and race, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, education, geography, disability,

language and immigration status. This requires pooling multiple years of data, or oversampling small populations.

Some Massachusetts cities and towns regularly analyze and report on SOGI data to better understand disparities and protective factors for LGBT residents. For example, in 2016, the Healthy Brookline report demonstrated that LGBTQ students were likely to hear derogatory remarks about their identities and experience depression.100 It also showed that mental health services are among the students’ protective factors, as a greater share of LGBTQ students saw mental health professionals than did their non-LGBTQ peers.

Following the Brookline example, we recommend:

- First, that the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH), which has been a great partner to us in developing the analysis for this report, regularly analyze and publish data collected in the state BRFSS and YRBS related to LGBT people.

- Second, that the state should invest in both collecting and publishing better data on anti-LGBT discrimination and violence victimization, given that the data currently available to the public from the Attorney General’s Office and the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination is extremely limited. Specifically, the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination and the Attorney General’s Office should work with Fenway Health’s Violence Recovery Program and other service providers to regularly publish data on the extent of anti-LGBT discrimination and violence victimization.

- Third, the Boston Public Health Commission and Boston Public Schools should publish its Boston Youth Risk Behavior Survey data on LGBT youth, and/or partner with local researchers to analyze and publish the data.

- Finally that data, whenever possible, should elucidate the intersection of multiple identities, including sexual orientation, gender identity, race, ethnicity, class, disability, age, immigration status and speaking a first language other than English. This may require pooling multiple years of data to have sufficient sample size. We also encourage agencies and researchers to look at differences within the data, for example comparing bisexual women, lesbian women, and heterosexual women. A growing body of research indicates that bisexuals experience the greatest rates of behavioral health burden, including depression and social anxiety, as well as the highest rates of cigarette smoking and other substance use. It is important to highlight bisexual health disparities in analysis and reporting.

ADDING SOGI QUESTIONS TO SURVEYS

In addition to reporting on currently collected data, state and local governments in Massachusetts should add SOGI questions to surveys where none currently exist. For example:

- The City of Boston Homeless Shelter Annual Homeless Census could ask SOGI questions to better understand and serve homeless LGBT people. Some data indicate that LGBTQ youth are overrepresented in homeless populations across the U.S. Is this true here? Are LGBTQ youth accessing homeless services at a proportionate level, and if not, why not?

- The Boston Survey of Children’s Health should ask SOGI questions of adolescents in order to better understand the experiences of LGBT youth.

Youth- and elder-serving agencies in Massachusetts should also collect SOGI data to better understand the extent to which LGBT people at the two ends of the age spectrum are accessing services. Data indicate that LGBT youth are overrepresented in foster care and juvenile justice populations, intersecting with racial and ethnic disparities. These and other youth serving agencies should collect and report on SOGI data, as the Massachusetts LGBTQ Youth Commission has been recommending for many years.101 - The Boston Public Health Commission’s Gonorrhea survey, Hepatitis C Virus survey, and Chlamydia survey should include SOGI questions because research has shown higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among gay and bisexual men and transgender women. LGBT people may also be more likely to become sexually active at earlier ages, which can put them at risk of STIs and pregnancy.

- More and more private employers are collecting voluntary, confidential SOGI data from employees. We strongly encourage all private sector employers to collect voluntary, confidential sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data from employees to document whether there are systemic disparities in employment and examine the intersection of SOGI with race/ethnicity, age, and other demographic variables.

CONCLUSION

While LGBT people in Massachusetts experience challenges, including striking disparities, Massachusetts is also home to some of the most cutting edge and innovative pro-LGBT social services, community resources and public policies. LGBT organizations work diligently across the Commonwealth to achieve equity and equality for LGBT people. Private corporations, health care organizations, institutions of higher learning and other organizations seek to promote inclusion and opportunity for LGBT residents of Massachusetts. These organizations and policies reflect the vision, strength and resilience of the LGBT community.

While there are no easy fixes, local and national work already under-way has begun to lay the paths forward. Drawing from the same perseverance, creativity and courage that have animated its efforts for decades, we have little doubt that the Massachusetts’ LGBT community, and its supporters, will continue to serve as national leaders in pursuing equality and equity for all LGBT people.

Go to Appendices

viii. Here, “LGBTQ community” refers to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer population and HIV-affected people. This is how the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs defines LGBTQ.

ix. Here, “LGBTQ community” refers to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer population and HIV-affected people.

x. See "From Stonewall to Today," in the Introduction